Codex Vaticanus

From Textus Receptus

(→Scribes and correctors: umlauts) |

(→In the Vatican Library) |

||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

[[Image:Angelo Mai.JPG|right|thumb|Angelo Mai prepared first edition of the New Testament text of the codex. It was publisched posthumoustly]] | [[Image:Angelo Mai.JPG|right|thumb|Angelo Mai prepared first edition of the New Testament text of the codex. It was publisched posthumoustly]] | ||

| - | In 1809 [[Napoleon]] brought it as a victory trophy to [[Paris]], but in 1815 it was returned to the [[Vatican Library]]. In that time, in Paris, German scholar [[Johann Leonhard Hug]] (1765-1846) saw it. Hug examined it together with the other best treasures of the Vatican, but he did not perceive the need of a new and full collation.<ref>J. L. Hug, "Commentario de antiquitate codicis Vaticani", Freiburg 1810. </ref><ref>John Leonard Hug, ''Writings of the New Testament'', translated by Daniel Guildford Wait (London 1827), p. 165. </ref> Cardinal [[Angelo Mai]] | + | In 1809 [[Napoleon]] brought it as a victory trophy to [[Paris]], but in 1815 it was returned to the [[Vatican Library]]. In that time, in Paris, German scholar [[Johann Leonhard Hug]] (1765-1846) saw it. Hug examined it together with the other best treasures of the Vatican, but he did not perceive the need of a new and full collation.<ref>J. L. Hug, "Commentario de antiquitate codicis Vaticani", Freiburg 1810. </ref><ref>John Leonard Hug, ''Writings of the New Testament'', translated by Daniel Guildford Wait (London 1827), p. 165. </ref> Cardinal [[Angelo Mai]] prepared an edition between 1828 and 1838, which, however, did not appear till 1857, three years after his death, and which was most unsatisfactory.<ref name = Nestle>[[Eberhard Nestle]] and William Edie, "Introduction to the Textual Criticism of the Greek New Testament", London, Edinburg, Oxford, New York, 1901, p. 60. </ref> It was issued in 5 volumes (1-4 volumes - Old Testament, 5 volume - New Testament). All lacunae of the codex were supplemented. Lacunae in the Acts and Pauline epistles were supplemented from the codex Vaticanus 1761, text of the Apocalypse from [[Uncial 046|Vaticanus 2066]], Mark 16:8-20 from [[Minuscule 151|Vaticanus Palatinus 220]], Acts 28:29 from Vaticanus 1761. Omitted verses: Matt. 12:47; Mark 15:28; Luke 22:43-44; 23:17.34; John 5:3.4; 7:53-8:11; 1 Peter 5:3; 1 John 5:7 were taken from popular Greek printed editions.<ref>Constantin von Tischendorf, ''Editio Octava Critica major'' (Lipsiae, 1884), vol. III, p. 364. </ref> Consequently, it was inaccurate and critically worthless edition of the whole manuscript. In 1859 was published improved Mai's edition.<ref name = Elliott>J. K. Elliott, ''A Bibliography of Greek New Testament Manuscripts'' (Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. 34. </ref> It was called by Tischendorf "Pseudo-facsimile". |

| + | |||

| + | In 1843 [[Constantin von Tischendorf|Tischendorf]] was permitted to make a facsimile of a few verses,<ref>"Besides the twenty-five readings Tischendorf observed himself, [[Angelo Mai|Cardinal Mai]] supplied him with thirty-four more his NT of 1849. His seventh edition of 1859 was enriched by 230 other readings furnished by Albert Dressel in 1855." (F. H. Scrivener, ''A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament'', Cambridge 1894, p. 111).</ref> in 1844 — [[Eduard de Muralt]] saw it,<ref>Muralt, "N. T. Gr. ad fidem codicis principis vaticani", Hamburg 1848, S. XXXV. </ref> and in 1845 — [[Samuel Prideaux Tregelles|S. P. Tregelles]] was allowed to observe several points which Muralt had overlooked. He often saw the codex, but "it was under such restrictions that it was impossible to do more than examine particular readings."<ref>S. P. Tregelles, ''An Introduction to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament'', London 1856, p. 162).</ref> | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

Revision as of 16:45, 1 August 2009

The Codex Vaticanus, (The Vatican, Bibl. Vat., Vat. gr. 1209; no. B or 03 Gregory-Aland, δ 1 von Soden), is one of the oldest and most valuable extant manuscripts of the Greek Bible. The codex is named for its place of housing in the Vatican Library.<ref>Bruce M. Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, "The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption and Restoration", Oxford University Press (New York - Oxford, 2005), p. 67. </ref> It is written in Greek, on 759 vellum leaves, with uncial letters, dated to the 4th century.<ref name=Aland>Kurt Aland, and Barbara Aland, "The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism", transl. Erroll F. Rhodes, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1995, p. 109. </ref> It is one of the best manuscripts of the Bible in Greek. Codex Sinaiticus is its only competitor. Until the discovery by Tischendorf of the Codex Sinaiticus, it was without a rival in the world.

Contents |

Contents

Vaticanus originally contained a complete copy of the Septuagint ("LXX") except for:

- 1-4 Maccabees

- Prayer of Manasseh

- Genesis 1:1 - 46:28a (31 leaves)

- Psalm 105:27 — 137:6b (20 leaves) are lost and have been filled by a later hand in the 15th century.<ref>Würthwein Ernst (1987). Der Text des Alten Testaments, Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, p. 84. </ref> 2 Kings 2:5-7.10-13 are also lost due to a tear in one of the pages.<ref> Fenry Barclay Swete, An Introduction to the Old Testament in Grek (Cambridge 1902), p. 126. </ref>

The order of the Old Testament books is as follows: Genesis to 2 Chronicles as normal, 1 Esdras, 2 Esdras (Ezra-Nehemiah), the Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Job, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Esther, Judith, Tobit, the minor prophets from Hosea to Malachi, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Baruch, Lamentations and the Epistle of Jeremiah, Ezekiel and Daniel. The order of the books differs from that which is followed in Codex Alexandrinus.<ref> Henry Barclay Swete, An Introduction to the Old Testament in Grek (Cambridge 1902), p. 127. </ref>

The extant New Testament of Vaticanus contains the Gospels, Acts, the General Epistles, the Pauline Epistles and the Epistle to the Hebrews (up to Heb 9:14, καθα[ριει); thus it lacks 1 and 2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon and Revelation. These missing leaves were replaced by a 15th century minuscule supplement (folios 760-768), they are catalogued separately as minuscule codex 1957.<ref name = Aland/> Possibly some apocryphal books of New Testament might have been included at the end (like codices Sinaiticus and Alexandrinus), although it is also possible that the Apocalypse was not included.<ref>Robert Waltz, Encyclopeida of Textual Criticism</ref>

Lacunae

- Omitted verses

The text of the New Testament lacks several passages:

- Matthew 12:47; 16:2b-3; Matthew 17:21; 18:11; Matthew 23:14;

- 7:16; 9:44.46; 11:26; 15:28; Mark 16:9-20;

- 17:36, 22:43-22:44|44;

- 5:4, John 7:53-8:11;

- Acts 8:37; 15:34, 24:7; 28:29;<ref>Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft: Stuttgart 2001), pp. 315, 388, 434, 444. </ref>

- Romans Romans 16:24.

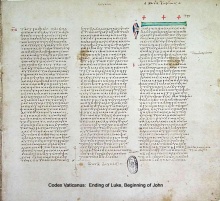

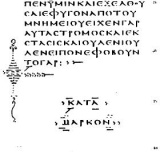

It does not have the ending of the Gospel of Mark, but the scribe was aware of it (in some manuscripts) and left an empty column after the Gospel of Mark. It is the only empty column in New Testament part of this codex.

- Omitted or not included phrases

- Matthew 5:44 ευλογειτε τους καταρωμενους υμας, καλως ποιειτε τοις μισουσιν υμας (bless those who curse you, do good to those who hate you);<ref>UBS3, p. 16. </ref>

- Matthew 10:37b και ο φιλων υιον η θυγατερα υπερ εμε ουκ εστιν μου αξιος (and he who loves son or dauther more than me is not worthy of me);

- Matthew 15:6 η την μητερα (αυτου) (or (his) mother);<ref>NA26, p. 41. </ref>

- Matthew 20:23 Unicode|και το βαπτισμα ο εγω βαπτιζομαι βαπτισθησεσθε (and be baptized with the baptism that I am baptized with), as in codices Sinaiticus, D, L, Z, Θ, 085, f1, f13, it, syrs, c, copsa.<ref>NA26, 56. </ref>

- Mark 10:7 omitted phrase και προσκολληθησεται προς την γυναικα αυτου (and be joined to his wife), as in codices Sinaiticus, Codex Athous Lavrensis, 892, ℓ 48, syrs, goth.<ref>UBS3, p. 164. </ref>

- Mark 10:19 — phrase μη αποστερησης omitted (as in codices K, W, Ψ, f1, f13, 28, 700, 1010, 1079, 1242, 1546, 2148, ℓ 10, ℓ 950, ℓ 1642, ℓ 1761, syrs, arm, geo) but added by a later corrector (B2).<ref>UBS3, p. 165.</ref>

- και ειπεν, Ουκ οιδατε ποιου πνευματος εστε υμεις; ο γαρ υιος του ανθρωπου ουκ ηλθεν ψυχας ανθρωπων απολεσαι αλλα σωσαι (and He said: "You do not know what manner of spirit you are of; for the Son of man came not to destroy men's lives but to save them) — omitted as in codices Sinaiticus C L Θ Ξ 33 700 892 1241 syr, copbo;<ref>NA26, p. 190.</ref>

- Luke 11:4 — αλλα ρυσαι ημας απο του πονηρου (but deliver us from evil) omitted. Omission is supported by the manuscripts: <math>\mathfrak{P}</math>75, Sinaiticus, L, f1 700 vg syrs copsa, bo, arm geo.<ref>UBS3, p. 256. </ref>

- Luke 23:34 — "And Jesus said: Father forgive them, they know not what they do." This omission is supported by the manuscripts <math>\mathfrak{P}</math>75, Sinaiticusa, D*, W, Θ, 0124, 1241, a, d, syrs, copsa, copbo.<ref>Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft: Stuttgart 2001), p. 154. </ref>

- Acts 27:16 — καυδα (name of island), this reading is supported only by <math>\mathfrak{P}</math>74, 1175, Old-Latin verions, Vulgate, and Peshitta.<ref>NA26, p. 403.</ref>

Additions

- In Matt. 27:49 codex contains added text: ἄλλος δὲ λαβὼν λόγχην ἒνυξεν αὐτοῦ τὴν πλευράν, καὶ ἐξῆλθεν ὖδορ καὶ αἳμα (the other took a spear and pierced His side, and immediately came out water and blood). This reading was derived from John 19:34 and occurs in other manuscripts of the Alexandrian text-type (א, C, L, Γ, 1010, 1293, pc, vgmss).<ref>Bruce M. Metzger (2001). "A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament", Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart: United Bible Societies, p. 59; NA26, p. 84; UBS3, p. 113.</ref>

Description

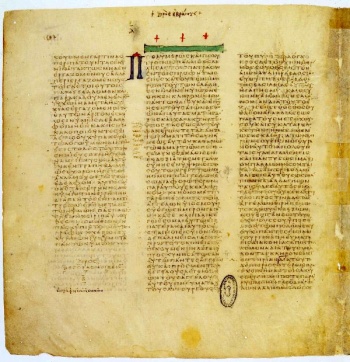

Originally it was composed of 820 parchment leaves as 71 leaves have been lost.<ref name = Kenyon>F. G. Kenyon, "Our Bible and the Ancient Manuscripts (4th ed.)", London 1939.</ref> Currently, it contains 617 leaves in Old Testament and 142 in New Testament. Parchment is fine and thin. The actual size of the pages is ,<ref name = Aland/> the original was bigger. The codex is written in three columns per page, 40-44 lines per page (in New Testament always 42), 16-18 letters per line. The letters are small and neat, without ornamentation or capitals.<ref name = Gregory>{Caspar René Gregory, Textkritik des Neuen Testaments (Leipzig 1900), Vol. 1, p. 32. </ref><ref name = Metzger/> The manuscript is one of the very few manuscripts and one of the very few Greek manuscripts of the New Testament to be written with three columns per page (the others being Codex Vaticanus 2061, Uncial 053, and Minuscule 460). Because it was not often used, it has survived to the present day in very good condition. Codex is comprised in a single quarto volume containing 759 thin and delicate vellum leaves.<ref name = Scrivener>F. H. A. Scrivener, Six Lectures on the Text of the New Testament and the Ancient Manuscripts (Cambridge, 1875), p. 26. </ref>

The Greek is written continuously with small neat writing, all the letters are equi-distant from each other, no word is separated from the other, each line seems only to be one word.<ref>John Leonard Hug, Writings of the New Testament, translated by Daniel Guildford Wait (London 1827), pp. 262-263. </ref> Punctuation is rare (accents and breathings have been added by a later hand) except for some blank spaces, diaeresis on initial iotas and upsilons, abbreviations of the nomina sacra and markings of OT citations. The OT citations were marked by inverted comma (>), just as in Alexandrinus. There are no enlarged initials, no stops or accents, no divisions into chapters or sections such as are found in later MSS.<ref>C. R. Gregory, "Canon and Text of the New Testament" (1907), p. 343.</ref>

The Gospels contain neither the Ammonian Sections nor the Eusebian Canons, but they are divided into peculiar numbered sections: Matthew has 170, Mark 61, Luke 152, and John 80. This system is found only in two other manuscripts, in Codex Zacynthius and in codex 579.<ref name = Metzger>Bruce M. Metzger, Manuscripts of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Greek Palaeography, New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991, p. 74. </ref> There are two system divisions in the Acts and the Catholic Epistles that differ from the Euthalian apparatus. In the Acts these sections are 36 (the same system has Codex Sinaiticus, Codex Amiatinus, and Codex Fuldensis) and according to the other system 69. 2 Peter has no numeration and it has been concluded that the system of divisions dates from a time before Epistle came to be commonly regarded as canonical.<ref>C. R. Gregory, "Textkritik des Neuen Testaments", Leipzig 1900, Vol. 1, pp. 33 nn. </ref> The chapters in the Pauline epistles are numbered continuously as the Epistles were regarded as comprising one book.

Text-type

In the Old Testament the type of text varies, with a good text in Book of Ezekiel, and a bad one in Book of Isaiah.<ref name = Metzger/> In Book of Judges the text differs substantially from that of the majority of manuscripts, but agrees with the Old Latin and Sahidic version and Cyril of Alexandria. In Book of Job it has the additional 400 half-verses from Theodotion, which are not in the Old Latin and Sahidic versions.<ref name = Metzger/> The text of the Old Testament was held by critics, such as Hort and Cornill, to be substantially that which underlies Origen's Hexapla edition, completed by him at Caesarea and issued as an independent work (apart from the other versions with which Origen associated it) by Eusebius and Pamphilus.<ref name = G.Kenyon83>Frederic G. Kenyon, "Handbook to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament", London2, 1912, p. 83.</ref>

In the New Testament the Greek text of the codex is a representative of the Alexandrian text-type. Aland placed it in Category I.<ref name = Aland/> In the Gospels of Luke and John it has been found to agree very closely with the text of Bodmer Papyrus 75; which is dated to the beginning of the 3rd century, and is hence at least 100 years older than the Codex Vaticanus. This demonstration that the Codex Vaticanus accurately reproduces a much earlier text in these two biblical books, had the effect of reinforcing the high reputation that the codex held amongst Biblical scholars (even, and illogically, outside of Luke and John). It also strongly suggested that it may have been copied in Egypt.<ref>Calvin L. Porter, Papyrus Bodmer XV (P75) and the Text of Codex Vaticanus, JBL 81 (1962), pp. 363-376. </ref> In the Pauline epistles there is a distinctly Western element.<ref name = Metzger/>

Some textual variants

In Luke 4:17 Vaticanus has textual variant ἀνοίξας (opened) together with the manuscripts A, L, W, Ξ, 33, 892, 1195, 1241, ℓ 547, syrs, h, pal, copsa, bo, against variant ἀναπτύξας (unrolled) supported by א, Dc, K, Δ, Θ, Π, Ψ, f1, f13, 28, 565, 700, 1009, 1010 and many other manuscripts.<ref>Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft: Stuttgart 2001), p. 114. </ref>

In John 12:28 it contains the unique textual variant δοξασον μου το ονομα. This variant is not supported by any other manuscript. Majority of the manuscripts have in this place: δοξασον σου το ονομα; some manuscripts have: δοξασον σου τον υιον (L, X, f1, f13, 33, 1241, pc, vg, syh mg, copbo).<ref>Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft: Stuttgart 2001), p. 202. </ref>

Provenance

The provenance and early history of the codex is uncertain.<ref name = Aland/> Rome (Hort), southern Italy, Alexandria (Kenyon,<ref name = G.Kenyon>Frederic G. Kenyon, "Handbook to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament", London2, 1912, p. 88.</ref> Burkitt<ref>F. C. Burkitt, "Texts and Studies", p. VIII-IX. </ref>), and Caesarea (T. C. Skeat) all having been suggested. Hort rested his argument mainly on certain spelling of proper names, such as Ισακ and Ιστραηλ, which show Western or Latin influence. As the second argument he used the fact that the chapter division in the Acts common to Sinaiticus and Vaticanus occurs in no other Greek manuscript, but is found in several manuscripts of the Latin Vulgate.<ref>Hort, Introduction to the New Testament in the Original Greek, pp. 264-267. </ref> Robinson easely disproved this argument by suggestion, that this system of chapters divisions was introduced into the Vulgate by Jerome himself, as a result of his studies at Caesarea.<ref>Robinson, Euthaliana, pp. 42, 101.</ref> According to Hort it was copied from a manuscript whose line length was 12-14 letters per line, because when the scribe of Codex Vaticanus made large omissions, they were typically 12-14 letters long.<ref>Brook F. Westcott and Fenton J. A. Hort, Introduction to the New Testament in the Original Greek (New York: Harper & Bros., 1882; reprint, Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1988), pp. 233-234. </ref>

Kenyon argumented: "It is noteworthy that the sectiuon numeration of the Pauline Epistles in B shows that it was copied from a manuscript in which the Epistle to the Hebrews was placed between Galatians and Ephesians; an arrangement which elsewhere occurs only in Sahidic version." <ref name = G.Kenyon84/> A connection with Egypt is also indicated by the order of the Pauline epistles and by the fact that, as in the Codex Alexandrinus, the titles of some of the books contain letters of a distinctively Coptic character, especially the Coptic mu, which is used not only in titles, but also very frequently at the ends of lines, when space is to be economized.<ref name = G.Kenyon84>Frederic G. Kenyon, "Handbook to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament", London2, 1912, p. 84.</ref> According to Metzger "the similarity of its text in significant portions of both Testaments with the Coptic versions and with Greek papyri, and the style of writing (notably the Coptic forms used in some of the titles) point rather to Egypt and Alexandria".<ref name = Metzger/>

There has been speculation that it had previously been in the possession of Cardinal Bessarion because the minuscule supplement has a text similar to one of Bessarion's manuscripts. According to Paul Canart's introduction to the recent facsimile edition, p. 5, the decorative initials added to the manuscript in the Middle Ages are reminiscent of Constantinopolitan decoration of the 10th century, but poorly executed, giving the impression that they were added in the 11th or 12th century. T. C. Skeat, a paleographer at the British Museum, first argued that Codex Vaticanus was among the 50 Bibles that the Emperor Constantine I ordered Eusebius of Caesarea to produce<ref>T. C. Skeat, "The Codex Sinaiticus, the Codex Vaticanus and Constantine", JTS 50 (1999), pp. 583–625.</ref>. The similarity of the text with the papyri and Coptic version (including some letter formation), parallels with Athanasius' canon of 367 suggest an Egyptian or Alexandrian origin.

It is dated to the first half of the 4th century. It is likely slightly older than Codex Sinaiticus, which also was transcribed in the 4th century. One argument is that Sinaiticus already has the, at that time, very new Eusebian Canon tables, but Vaticanus doesn't. Another is the slightly more archaic style of Vaticanus, and more complete absence of ornamentation, caused it to be regarded as slightly the older than Sinaiticus.<ref name = Kenyon>F. G. Kenyon, "Our Bible and the Ancient Manuscripts (4th ed.)", London 1939.</ref>

Scribes and correctors

The manuscript was written by three scribes, two of them wrote the Old Testament and one the New Testament (B1, B2, B3).<ref name = Aland/> Two correctors worked on the manuscript, one (B2) about contemporary with the scribes, the other (B3) of about the 10th or 11th century.<ref name = Metzger/> The original writing was later retraced by a 10th (or 11th) century scribe.

There are plenty of the itacistic faults, especially the exchange of ει for ι.<ref>C. R. Gregory, "Canon and Text of the New Testament" (1907), pp. 343-344.</ref>

The manuscript contains mysterious small horizontally aligned double dots (so called "umlauts") in the margin of the columns and are scattered all over the New Testament.<ref group="n">List of umlauts in New Testament of the Codex Vaticanus</ref> There are 795 of these in the text and around another 40 that are uncertain. The date of these markings are disputed among scholars and are discussed in a link below. Two such "umlauts" can be seen in the left margin of the first column (top image). Tischendorf reflected upon their meaning, but without any success.<ref name = NTVaticanumXXI>Constantin von Tischendorf, Novum Testamentum Vaticanum, Leipzig 1867, p. XXI. </ref> He pointed on several places where these umlauts were used - at the ending of the Gospel of Mark, 1 Thess 2:14; 5:28; Heb 4:16; 8:1.<ref name = NTVaticanumXXI/> The meaning of these umlauts was recognized in 1995 by Philip Payne. Payne suggested that these umlauts indicate lines where another textual variant was known to the person who wrote the umlauts. The umlauts are marked places of textual uncertainty.<ref>Philip B. Payne and Paul Canart "The Originality of Text-Critical Symbols in Codex Vaticanus.", Novum Testamentum 42 (2000) 105 - 113 </ref><ref>Philip B. Payne and Paul Canart "The Text-Critical Function of the Umlauts in Vaticanus, with Special Attention to 1 Corinthians 14.34-35: A Response to J. Edward Miller.", JSNT 27 (2004) 105-112 </ref><ref>G. S. Dykes, Using the „Umlauts” of Codex Vaticanus to Dig Deeper, 2006. See: Codex Vaticanus Graece. The Umlauts.</ref>

On page 1512, next to Hebrews 1:3, the text contains an interesting marginal note, "Fool and knave, can't you leave the old reading alone and not alter it!"—"ἀμαθέστατε καὶ κακέ, ἄφες τὸν παλαιόν, μὴ μεταποίει" which suggests that inaccurate copying, either intentional or unintentional, was a known problem in scriptoriums.<ref name=marginal_note>Codex Vaticanus Graece 1209, B/03, {{#invoke:citation/CS1|citation |CitationClass=web }}</ref> The uppermost picture of this article shows the page where this remark is found (In the middle of the yellow page, between 1st and 2nd column).

In the Vatican Library

The manuscript has been housed in the Vatican Library (founded by Pope Nicholas V in 1448) for as long as it has been known, appearing in its earliest catalog of 1475 and in the 1481 catalogue. In catalog from 1481 it was described as a "Biblia in tribus columnis ex memb."<ref name = Kenyon/>

In the 16th century it became known to scholars in result of the correspondence between Erasmus and the prefects of the Vatican Library, successively Paulus Bombasius, and Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda. In 1521, Bombasius was consulted by Erasmus as to whether the Codex Vaticanus contained the Comma Johanneum, and Bombasius supplied a transcript of 1 John 4 1-3 and 1 John 5 7-11 to show that it did not. Sepúlveda in 1533 cross-checked all places where Erasmus's New Testament (the Textus Receptus) differed from the Vulgate, and supplied Erasmus with 365 readings where the Codex Vaticanus supported the latter.<ref group="n">We do not know nothing about these 365 readings except one. Erasmus in his Adnotationes do Acts 27:16 wrote that according to the Codex from the Library Pontifici name of the island is καυδα (Cauda), not κλαυδα (Clauda) as in his Novum Testamentum. See: Erasmus Desiderius, Erasmus’ Annotations on the New Testament: Acts – Romans – I and II Corinthians, ed. A. Reeve and M. A. Sceech, (Brill: Leiden 1990), p. 931. Andrew Birch was the first, who identified this note with 365 readings of Sepulveda. </ref> Consequently, the Codex Vaticanus acquired the reputation of being an old Greek manuscript that agreed rather with the Vulgate rather than with the Textus Receptus. It would not be till much later that scholars realised that it conformed to a consistent text that differed from both the Vulgate and the Textus Receptus; a text that could also be found in other known early Greek manuscripts, such as the Codex Regius (L) in the French Royal Library.<ref>S. P. Tregelles, An Introduction to the Critical study and Knowledge of the Holy Scriptures, London 1856, p. 108. </ref>

In 1669 a collation was made by Giulio Bartolocci, librarian of the Vatican, but it was not published, and was never used until Scholz in 1819 found a copy of it in the Royal Library at Paris. This collation was imperfect (revised in 1862). Another collation was made in 1720 for Bentley by Mico, and revised by Rulotta. This collation was published in 1799.<ref name = G.Kenyon78>Frederic G. Kenyon, "Handbook to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament", London2, 1912, p. 78.</ref> A further collation was made by Andrew Birch, who edited in 1798 in Copenhagen some textual variants for the Acts of the Apostles and the Epistles,<ref>Andreas Birch, Variae Lectiones ad Textum Actorum Apostolorum, Epistolarum Catholicarum et Pauli (Copenhagen 1798).</ref> in 1800 for the Apocalypse,<ref>Andreas Birch, Variae lectiones ad Apocalypsin (Copenhagen 1800).</ref> in 1801 for the Gospels.<ref>Andreas Birch, Variae Lectiones ad Textum IV Evangeliorum (Copenhagen 1801).</ref> They were incomplete and included together with the textual variants from the other manuscripts.<ref name = G.Kenyon/> Many of them were false. Andreas Birch reproached for Mill and Wettstein, that they falso citatur Vaticanus, and gave as example Luke 2:38 - Ισραηλ instead of Ιερουσαλημ.<ref>Andreas Birch, Variae Lectiones ad Textum IV Evangeliorum (Copenhagen 1801), p. XXVII. </ref>

Before the 19th century no scholar was allowed to study or edit it and scholars were not aware about real value of the codex. In that time codex was under suspicion of having been heavily interpolated by the Latin tradition of text.<ref name = Martini>Carlo Maria Martini, La Parola di Dio Alle Origini della Chiesa, (Rome: Bibl. Inst. Pr. 1980), p. 287.</ref> John Mill in his Prolegomena (1707) wrote: "in Occidentalium gratiam a Latino scriba exaratum" (written by a Latin scribe for the western world). He did not think that was important to collate this manuscript.<ref name = Martini/> Wettstein would have liked to know the readings of the codex not because he thought that they could have been of any help to him for difficult textual decisions. According to him this codex had no authority whatsoever (sed ut vel hoc constaret, Codicem nullus esse auctoris).<ref>Johann Jakob Wettstein, Novum Testamentum Graecum, Tomus I (Amstelodami, 1751), p. 24. </ref> In 1751 Wettstein produced the first list of the New Testament manuscripts, Codex Vaticanus received symbol B (because of its age) and took second position on this list (Alexandrinus received A, Ephraemi - C, Bezae - D, etc.).<ref>Johann Jakob Wettstein, Novum Testamentum Graecum, Tomus I (Amstelodami, 1751), p. 22. </ref> Untill to the discovering of Codex Sinaiticus (designated by א), Vaticanus occupied second position on the list of New Testament manuscripts.<ref>Constantin von Tischendorf, Novum Testamentum Graece: Editio Octava Critica Maior (Leipzig: 1869).</ref>

Griesbach produced a list of nine manuscripts which were to be asigned to the Alexandrian text: C, L, K, 1, 13, 33, 69, 106, and 118.<ref>J. J. Griesbach, Novum Testamentum Graecum, vol. I (Halle, 1777), prolegomena. </ref> Codex Vaticanus was not in this list. In 1796 in second edition of his Greek NT Griesbach added Codex Vaticanus as witness to the Alexandrian text in Mark, Luke, and John. He still thought that the first half of Matthew represents the Western text-type.<ref>J. J. Griesbach, Novum Testamentum Graecum, 2 editio (Halae, 1796), prolegomena, p. LXXXI. See Edition from 1809 (London)</ref>

In 1809 Napoleon brought it as a victory trophy to Paris, but in 1815 it was returned to the Vatican Library. In that time, in Paris, German scholar Johann Leonhard Hug (1765-1846) saw it. Hug examined it together with the other best treasures of the Vatican, but he did not perceive the need of a new and full collation.<ref>J. L. Hug, "Commentario de antiquitate codicis Vaticani", Freiburg 1810. </ref><ref>John Leonard Hug, Writings of the New Testament, translated by Daniel Guildford Wait (London 1827), p. 165. </ref> Cardinal Angelo Mai prepared an edition between 1828 and 1838, which, however, did not appear till 1857, three years after his death, and which was most unsatisfactory.<ref name = Nestle>Eberhard Nestle and William Edie, "Introduction to the Textual Criticism of the Greek New Testament", London, Edinburg, Oxford, New York, 1901, p. 60. </ref> It was issued in 5 volumes (1-4 volumes - Old Testament, 5 volume - New Testament). All lacunae of the codex were supplemented. Lacunae in the Acts and Pauline epistles were supplemented from the codex Vaticanus 1761, text of the Apocalypse from Vaticanus 2066, Mark 16:8-20 from Vaticanus Palatinus 220, Acts 28:29 from Vaticanus 1761. Omitted verses: Matt. 12:47; Mark 15:28; Luke 22:43-44; 23:17.34; John 5:3.4; 7:53-8:11; 1 Peter 5:3; 1 John 5:7 were taken from popular Greek printed editions.<ref>Constantin von Tischendorf, Editio Octava Critica major (Lipsiae, 1884), vol. III, p. 364. </ref> Consequently, it was inaccurate and critically worthless edition of the whole manuscript. In 1859 was published improved Mai's edition.<ref name = Elliott>J. K. Elliott, A Bibliography of Greek New Testament Manuscripts (Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. 34. </ref> It was called by Tischendorf "Pseudo-facsimile".

In 1843 Tischendorf was permitted to make a facsimile of a few verses,<ref>"Besides the twenty-five readings Tischendorf observed himself, Cardinal Mai supplied him with thirty-four more his NT of 1849. His seventh edition of 1859 was enriched by 230 other readings furnished by Albert Dressel in 1855." (F. H. Scrivener, A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, Cambridge 1894, p. 111).</ref> in 1844 — Eduard de Muralt saw it,<ref>Muralt, "N. T. Gr. ad fidem codicis principis vaticani", Hamburg 1848, S. XXXV. </ref> and in 1845 — S. P. Tregelles was allowed to observe several points which Muralt had overlooked. He often saw the codex, but "it was under such restrictions that it was impossible to do more than examine particular readings."<ref>S. P. Tregelles, An Introduction to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament, London 1856, p. 162).</ref>

"They would not let me open it without searching my pockets, and depriving me of pen, ink, and paper; and at the same time two prelati kept me in constant conversation in Latin, and if I looked at a passage too long, they would snatch the book out of my hand".<ref>S. P. Tregelles, "A Lecture on the Historic Evidence of the Authorship and Transmission of the Books of the New Testament", London 1852, pp. 83-85.</ref>

Tregelles left Rome after five months without accomplishing his object. During a large part of the 19th century, the authorities of the Vatican Library obstructed scholars who wished to study the codex in detail. Henry Alford in 1849 wrote: “It has never been published in facsimile (!) nor even thoroughly collated (!!).” <ref>H. Alford, The Greek Testament. The Four Gospels, London 1849, p. 76. </ref> Scrivener in 1861 commented:

"To these legitimate sources of deep interest must be added the almost romantic curiosity which has been excited by the jealous watchfulness of its official guardians, with whom an honest zeal for its safe preservation seems to have now degenerated into a species of capricious wilfulness, and who have shewn a strange incapacity for making themselves the proper use of a treasure they scarcely permit others more than to gaze upon". <ref>F. H. A. Scrivener, "A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament", Cambridge 1861, p. 85. </ref> It (...) "is so jealously guarded by the Papal authorities that ordinary visitors see nothing of it but the red morocco binding".<ref name = Scrivener/>

Thomas Law Montefiore (1862):

"The history of the Codex Vaticanus B, No. 1209, is the history in miniature of Romish jealousy and exclusiveness.” <ref>T.L. Montefiore, Catechesis Evangelica; bring Questions and Answers based on the “Textus Receptus”, (London, 1862), p. 272. </ref>

Burgon was permitted to examine codes for an hour and a half in 1860, on consulting it for 16 passages of the codex.<ref>F. H. A. Scrivener, A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, (London 1894), vol. 1, p. 114. </ref> Burgon was a supporter of the Textus Receptus and for him Codex Vaticanus, as well as codices Sinaiticus and Codex Bezae, was the most corrupt documents extant. Each of these three codices "clearly exhibits a fabricated text - is the result of arbitrary and reckless recension."<ref>Burgon, Revision Revised, p. 9. </ref> The two most weighty of these three codices, א and B, he likens to the "two false witnesses" of Matthew 26:60.<ref>Burgon, Revised Revision, p. 48. </ref>

Henry Alford in 1861, and his secretary Mr. Cure in 1862 collated and verrified doubtfull passages (in several imperfect collations), which in facsimile editions were published with errors.<ref>D. Alford, Life by my Widow, pp. 310, 315. </ref>

In 1889-1890 a photographic facsimile of the whole manuscript was made and published by Giuseppe Cozza-Luzi, in three volumes.<ref name = Nestle/> Another facsimile of the New Testament text was published in 1904 in Milan.<ref>Bruce M. Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, "The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption and Restoration", Oxford University Press (New York - Oxford, 2005), p. 68. </ref> As a result the codex became widely available.

Importance

Codex Vaticanus is one of the most important manuscripts for the text of the Septuagint and Greek New Testament, it is a leading member of the Alexandrian text-type. It was heavily used by Westcott and Hort in their edition, The New Testament in the Original Greek (1881). In the Gospels, it is the most important witness of the text, in Acts and Catholic epistles, equal to Codex Sinaiticus, in Pauline epistles it has some Western readings and the value of its text is a little lower than of the Codex Sinaiticus. Unfortunately the manuscript is not complete. Aland notes: "B is by far the most significant of the uncials.<ref name = Aland/>

See also

Notes

References

Further reading

- Burnett Hillman Streeter, "The Four Gospels. A Study of Origins", Oxford 1924.

- S. Kubo, "P72 and the Codex Vaticanus", S & D XXVII, Salt Lake City, 1965.

- C. M. Martini, "Il problema della recentionalita del Codice B alla Luce del Papiro Bodmer XIV (P75)", Analecta biblica 26, Roma, 1966.

- Bruce M. Metzger, "Manuscripts of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Greek Palaeography", Oxford University Press, New York – Oxford 1981.

- J. Edward Miller, "Some Observations on the Text-Critical Function of the Umlauts in Vaticanus, with Special Attention to 1. Corinthians 14.34-35", JSNT 26 (2003) 217-236 [Miller disagrees with Payne on several points. He notes and uses this website.]

- Curt Niccum, "The voice of the MSS on the Silence of the Women: ...", NTS 43 (1997), pp. 242–255.

- Janko Sagi, "Problema historiae codicis B", Divius Thomas 1972, 3-29.

- T. C. Skeat, "The Codex Vaticanus in the 15th Century", JTS 35 (1984), pp. 454-465; T. C. Skeat, J. K. Elliott, The collected biblical writings of T.C. Skeat, Brill 2004, ss. 120-134.

- Philip B. Payne "Fuldensis, Sigla for Variants in Vaticanus and 1 Cor 14.34-5", NTS 41 (1995) 251-262 [Payne discovered the first umlaut while studying this section.]

- Philip B. Payne and Paul Canart, "The Originality of Text-Critical Symbols in Codex Vaticanus", Novum Testamentum Vol. 42, Fasc. 2 (April, 2000), pp. 105–113.

- Philip B. Payne and Paul Canart, "The Text-Critical Function of the Umlauts in Vaticanus, with Special Attention to 1 Corinthians 14.34-35: A Response to J. Edward Miller", JSNT 27 (2004) 105-112 [Payne still thinks, contra Miller, that the combination of a bar plus umlaut has a special meaning.]

- Constantin von Tischendorf, Novum Testamentum Vaticanum, Lipsiae 1867.

- C. Vercellonis, J. Cozza, "Bibliorum Sacrorum Graecus Codex Vaticanus", Roma 1868.

- James W. Voelz, "The Greek of Codex Vaticanus in the Second Gospel and Marcan Greek", Novum Testamentum 47 (2005), 3, pp. 209–249.

External links

Pseudo-Facsimiles

- Center for the Study of NT Manuscripts. Codex Vaticanus

- Codex Vaticanus NT Edition in PDF format. 16MB download

Articles

- Codex Vaticanus at the Encyclopedia of Textual Criticism

- Universität Bremen Detailed description of "Codex Vaticanus" with many images and discussion of the "umlauts".