Revelation 16:5

From Textus Receptus

Revelation 16:5 And I heard the angel of the waters say, Thou art righteous, O Lord, which art, and wast, and shalt be, because thou hast judged thus.

Textus Receptus

- 1514 (Complutensian Polyglot)

- 1516 (Erasmus 1st)

- 1519 (Erasmus 2nd)

- 1522 (Erasmus 3rd)

- 1527 (Erasmus 4th)

- 1535 (Erasmus 5th)

- 1546 (Stephanus 1st)

- 1549 (Stephanus 2nd)

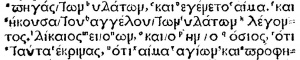

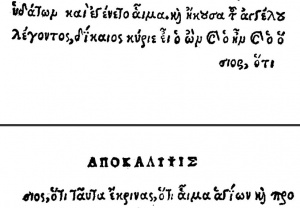

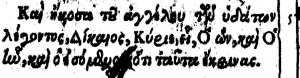

- 1550 καὶ ἤκουσα τοῦ ἀγγέλου τῶν ὑδάτων λέγοντος Δίκαιος Κύριε, εἶ ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἦν καὶ ὁ ὅσιος ὅτι ταῦτα ἔκρινας (Stephanus 3rd)

- 1551 (Stephanus 4th)

- 1565 (Beza 1st)

- 1565 (Beza Octavo 1st)

- 1567 (Beza Octavo 2nd)

- 1580 (Beza Octavo 3rd)

- 1582 (Beza 2nd)

- 1588 (Beza 3rd)

- 1590 (Beza Octavo 4th)

- 1598 καὶ ἤκουσα τοῦ ἀγγέλου τῶν ὑδάτων λέγοντος, Δίκαιος, Κύριε, εἶ ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἦν καὶ ὁ ἐσόμενος, ὅτι ταῦτα ἔκρινας· Revelation 16:5 Beza 1598 (Beza)

- 1604 (Beza Octavo 5th)

- 1624 (Elzevir)

- 1633 (Elzevir)

- 1641 (Elzevir)

- 1841 Scholz)

- 1894 (Scrivener)

- 2000 (Byzantine/Majority Text)

P47 is slightly worn, the Greek text which Beza used was greatly worn. This is so noted by Beza himself in his footnote on Revelation 16:5 as he gives reason for his conjectural emendation. (See Below )

Erasmus 1522 and Stephanus 1550 also have "kai," and this was before P47 was known to scholars, so there was more than just "one manuscript standing out.

Other Greek

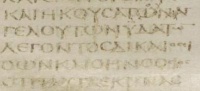

- 250 και ηκουσα του αγγελου των υδατων λεγοντος δικαιος ει ο ων και ος ην και οσιος̣ οτι ταυτα εκρινας (Papyrus 47) Papyrus 47 conatins "και"

- καί ἀκούω ὁ ἄγγελος ὁ ὕδωρ λέγω δίκαιος εἰμί ὁ εἰμί καί ὁ εἰμί ὁ ὅσιος ὅτι οὗτος κρίνω Tischendorf 8th Ed

- καὶ ἤκουσα τοῦ ἀγγέλου τῶν ὑδάτων λέγοντος, δίκαιος εἶ, ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἦν ὁ ὅσιος, ὅτι ταῦτα ἔκρινας Westcott / Hort, UBS4

English Versions

- 1395 [And the thridde aungel... seide,] Just art thou, Lord, that art, and that were hooli, that demest these thingis; (Wycliffe)

- 1526 And I herde an angell saye: lorde which arte and wast thou arte ryghteous and holy because thou hast geve soche iudgmentes (Tyndale)

- 1535 And I herde an angel saye: LORDE which art and wast, thou art righteous and holy, because thou hast geue soche iudgmentes, (Coverdale)

- 1540 And I herde an Angell saye: Lorde, whych arte and wast, thou arte ryghteous & holy, because thou hast geuen soche iudgementes, (Great Bible)(Coverdale)

- 1549 And I heard an angel say: Lord which art & wast, thou art rightuous & holy, because thou hast geuen such iudgementes, (Matthew's Bible by John Rogers)

- 1557 And I heard the Angel of the waters say, Lord, thou art iust, Which art, and Which wast: and Holy, because thou hast iudged these things. (Geneva)

- 1568 And I hearde the angell of the waters say: Lorde, which art, and wast, thou art ryghteous & holy, because thou hast geuen such iudgementes: (Bishop’s)

- 1833 And I heard the angel of the waters say, Thou art righteous, O Lord, who art, and wast, and wilt be, because thou hast judged thus. (Websters)

- 1851 And I heard the angel of the waters say: Righteous art thou, who art and who wast, and art holy; because thou hast done this judgment. (Murdock Translation by James Murdock)

- 1898 and I heard the messenger of the waters, saying, `righteous, O Lord, art Thou, who art, and who wast, and who shalt be, because these things Thou didst judge, (Young's Literal Translation)

- 1982 And I heard the angel of the waters saying: 'You are righteous, O Lord, The One who is and who was and who is to be, Because You have judged these things. (New King James Version)

Foreign Language Translations

Albanian

- Dhe dëgjova engjëllin e ujërave duke thënë: Ti je i drejtë, o Zot, që je që ishe dhe që do të vish, i Shenjti që gjykoi këto gjëra.

Armenian

Լսեցի ջուրերուն հրեշտակը՝ որ կ՚ըսէր. «Արդա՛ր ես, դուն՝ որ ես եւ որ էիր, ու սո՛ւրբ ես՝ որ ա՛յսպէս դատեցիր,

Arabic

Basque

- Eta ençun neçan vretaco Aingueruä, cioela, Iusto aiz Iauna, Aicena eta Incena eta Saindua: ceren gauça hauc iugeatu baitituc: (Navarro-Labourdin)

Bulgarian

- И чух ангела на водите да казва: Праведен си Ти, Пресвети, Който си, и Който си бил, загдето си отсъдил така;

Czech

- 1613 Nebo tři jsou, kteříž svědectví vydávají na nebi: Otec, Slovo, a Duch Svatý, a ti tři jedno jsou. bible of Kralice

Croatian

- I začujem anđela voda gdje govori: Pravedan si, Ti koji jesi i koji bijaše, Sveti, što si tako dosudio!

French

- 1744 Et j'entendis l'ange des eaux, qui disait: Tu es juste, Seigneur, QUI ES, et QUI ÉTAIS, et QUI SERAS saint, parce que tu as exercé ces jugements. (Ostervald)

- 1744 Et j'entendis l'Ange des eaux, qui disait : Seigneur, QUI ES, QUI ÉTAIS, et QUI SERAS, tu es juste, parce que tu as fait un tel jugement. (Martin)

- Et j'entendis l'ange des eaux, disant: Tu es juste, toi qui es et qui étais, le Saint, parce que tu as ainsi jugé; (Darby)

- 1864 (Augustin Crampon)

- 1910 (Louis Segond)

German

- 1545 Und ich horte den Angel der Wasser sagen: herr, du bist gerecht, der da ist und der da war, und heilig, dab du solches geurteilt hast (Luther)

- 1871 Und ich hörte den Engel der Wasser sagen: Du bist gerecht, der da ist und der da war, der Heilige, (O. Fromme) daß du also gerichtet (O. geurteilt) hast. (Elberfelder)

Italian

- 1927 E udii l’angelo delle acque che diceva: Sei giusto, tu che sei e che eri, tu, il Santo, per aver così giudicato. (Riveduta Bible)

Latin

- et audivi angelum aquarum dicentem iustus es qui es et qui eras sanctus quia haec iudicasti (Vulgate)

Russian

- 1876 И услышал я Ангела вод, который говорил: праведен Ты, Господи, Который еси и был, и свят, потому что так судил; (RUSV)

- Russian Transliteration of the Greek

- (Church Slavonic)

Theodore Beza

Beza himself comments on this change in a marginal note of his Greek New Testament:

- "And shall be": The usual publication is "holy one," which shows a division, contrary to the whole phrase which is foolish, distorting what is put forth in scripture. The Vulgate, however, whether it is articulately correct or not, is not proper in making the change to "holy," since a section (of the text) has worn away the part after "and," which would be absolutely necessary in connecting "righteous" and "holy one." But with John there remains a completeness where the name of Jehovah (the Lord) is used, just as we have said before, 1:4; he always uses the three closely together, therefore it is certainly "and shall be," for why would he pass over it in this place? And so without doubting the genuine writing in this ancient manuscript, I faithfully restored in the good book what was certainly there, "shall be." So why not truthfully, with good reason, write "which is to come" as before in four other places, namely 1:4 and 8; likewise in 4:3 and 11:17, because the point is the just Christ shall come away from there and bring them into being: in this way he will in fact appear setting in judgment and exercising his just and eternal decrees.

(Theodore Beza, Nouum Sive Nouum Foedus Iesu Christi, 1589. Translated into English from the Latin footnote.)

D. A. Waite

D. A. Waite says that modern English versions are theologically deficient at Revelation 16:5 for the removal of "and shalt be" (Defending the KJB, p. 170). Waite wrote: “The removal of ‘and shalt be’ puts in doubt the eternal future of the Lord Jesus Christ. This is certainly a matter of doctrine and theology” (p. 170).

John Wordsworth

Dr. John Wordsworth (who edited and footnoted a three volume critical edition of the New Testament in Latin) pointed out that the like phrase in Revelation 1:4 "which is, and which was, and which is to come;" sometimes is rendered in Latin as "qui est et qui fuisti et futurus es" instead of the Vulgate "qui est et qui erat et qui uenturus est." (John Wordsworth, Nouum Testamentum Latine, vol.3, 422 and 424.)

Wordsworth also points out that in Revelation 16:5, Beatus of Liebana (who compiled a commentary on the book of Revelation) uses the Latin phrase "qui fuisti et futures es." This gives some additional evidence for the Greek reading by Beza (although he apparently drew his conclusion for other reasons). Beatus compiled his commentary in 786 AD. Furthermore, Beatus was not writing his own commentary. Instead he was making a compilation and thus preserving the work of Tyconius, who wrote his commentary on Revelation around 380 AD (Aland and Aland, 211 and 216. Altaner, 437. Wordsword, 533.). So, it would seem that as early as 786, and possibly even as early as 380, their was an Old Latin text which read as Beza's Greek text does.

Will Kinney

- See Also Revelation 16:5 "and shalt be" by Will Kinney

- "The King James Bible translators did not slavishly follow Beza’s Greek text, but after much prayer, study and comparison, did include Beza’s reading of “and shalt be” in Revelation 16:5. We do not know what other Greek texts the KJB translators possessed at that time that may have helped them in their decisions. They then passed this reading on to future generations in the greatest Bible ever written. Since God has clearly placed His mark of divine approval upon the KJB throughout the last 400 years, I trust that He providentially guided the translators to give us His true words."

Jack Moorman

- "The KJV reading is in harmony with the four other places in Revelation where this phrase is found…. Indeed Christ is the Holy One, but in the Scriptures of the Apostle John the title is found only once (1 John. 2:20), and there, a totally different Greek word is used. The Preface to the Authorised Version reads: “with the former translations diligently compared and revised”. The translators must have felt there was good reason to insert these words though it ran counter to much external evidence. They obviously did not believe the charge made today that Beza inserted it on the basis of conjectural emendation. They knew that they were translating the Word of God, and so do we. The logic of faith should lead us to see God’s guiding providence in a passage such as this." —

Jack Moorman in When the KJV Departs from the So-Called Majority Text (Bible for Today: 1988), pg. 102.

Edward F. Hills

According to Edward F. Hills, this KJV rendering “shalt be” came from a conjectural emendation interjected into the Greek text by Beza (Believing Bible Study, pp. 205-206). Hills again acknowledged that Theodore Beza introduced a few conjectural emendations in his edition of the Textus Receptus with two of them kept in the KJV, one of them at Revelation 16:5 shalt be instead of holy.

- Like Calvin, Beza introduced a few conjectural emendations into his New Testament text. In the providence of God, however, only two of these were perpetuated in the King James Version, namely, Romans 7:6 that being dead wherein instead of being dead to that wherein, and Revelation 16:5 shalt be instead of holy. In the development of the Textus Receptus the influence of the common faith kept conjectural emendation down to a minimum. [1]

Edward Hills identified the KJV reading at Revelation 16:5 as “certainly erroneous” and as a “conjectural emendation by Beza” (Believing Bible Study, p. 83).

William W. Combs

William W. Combs maintained: “Beza simply speculated (guessed), without any evidence whatsoever, that the correct reading was ‘shall be’ instead of ‘holy one’” (Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal, Fall, 1999, p. 156).

J. I. Mombert

J. I. Mombert listed Revelation 16:5 as one of the places where he maintained that “the reading of the A. V. is supported by no known Greek manuscript whatever, but rests on an error of Erasmus or Beza” (Hand-book, p. 389).

Bullinger

Bullinger indicated that 1624 edition of the Elzevirs’ Greek text has “the holy one” at this verse (Lexicon, p. 689). In his commentary on the book of Revelation, Walter Scott asserted that the KJV’s rendering “shalt be” was an unnecessary interpolation and that the KJV omitted the title “holy One” (p. 326).

Bruce Metzger

Bruce Metzger defines this term as,

- The classical method of textual criticism . . . If the only reading, or each of several variant readings, which the documents of a text supply is impossible or incomprehensible, the editor's only remaining resource is to conjecture what the original reading must have been. A typical emendation involves the removal of an anomaly. It must not be overlooked, however, that though some anomalies are the result of corruption in the transmission of the text, other anomalies may have been either intended or tolerated by the author himself. Before resorting to conjectural emendation, therefore, the critic must be so thoroughly acquainted with the style and thought of his author that he cannot but judge a certain anomaly to be foreign to the author's intention. (Metzger, The Text Of The New Testament, 182.)

From this, we learn the following.

- 1). Conjectural emendation is a classical method of textual criticism often used in every translation or Greek text when there is question about the authenticity of a particular passage of scripture.

- 2). There should be more than one variant in the passage in question.

- 3). The variant in question contextually should fit and should be in agreement with the style of the writer.

John Gill

John Gill's Exposition of the Bible says;

- The Alexandrian copy, and most others, and the Vulgate Latin and Syriac versions, read "holy", instead of "shalt be"; for the purity and holiness of Christ will be seen in the judgments which he will exercise, as follows:

- because thou hast judged thus; or "these things"; or "them", as the Ethiopic version reads; that is, has brought these judgments upon the men signified by rivers and fountains, and made great havoc and slaughter of them, expressed by their becoming blood; the justice of which appears from the following reason.

See Also

- Revelation 16:5 And Shalt Be

- Revelation 16:5 "and shalt be" by Will Kinney

- Conjecture (textual criticism)

References

- 1. Edward F. Hills, The King James Version Defended, p. 208