Wycliffe's Bible

From Textus Receptus

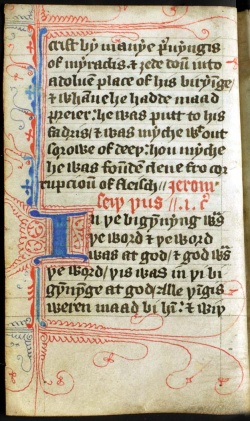

Wyclif's Bible is the name now given to a group of Bible translations into Middle English that were made under the direction of, or at the instigation of, John Wycliffe. They appeared over a period from approximately 1382 to 1395.[1] These Bible translations were the chief inspiration and chief cause of the Lollard movement, a pre-Reformation movement that rejected many of the distinctive teachings of the Roman Catholic Church. In the early Middle Ages, most Western Christian people encountered the Bible only in the form of oral versions of scriptures, verses and homilies in Latin (other sources were mystery plays, usually conducted in the vernacular, and popular iconography). Though relatively few people could read at this time, Wycliffe’s idea was to translate the Bible into the vernacular.

“[…] it helpeth Christian men to study the Gospel in that tongue in which they know best Christ’s sentence.”[2]

Long thought to be the work of Wycliffe himself, it is now generally believed that the Wycliffite translations were the work of several hands. Nicholas of Hereford is known to have translated a part of the text; John Purvey and perhaps John Trevisa are names that have been mentioned as possible authors. The translators worked from the Vulgate, the Latin Bible that was the standard Biblical text of Western Christianity, and the text coforms fully with Catholic teaching. They included in the testaments those works which would later be called deuterocanonical along with 3 Esdras which is now called 2 Esdras and Paul's epistle to the Laodiceans.

Although unauthorized, the work was popular. Wycliffite Bible texts are the most common manuscript literature in Middle English. Over 250 manuscripts of the Wycliffite Bible survive; its nearest competitor is the essay on the "Prick of Conscience" that survives in 117 copies.

Surviving copies of the Wycliffite Bible fall into two broad textual families, an "early" version and a later version. Both versions are flawed by a slavish regard to the word order and syntax of the Latin originals; the later versions give some indication of being revised in the direction of idiomatic English. A wide variety of Middle English dialects are represented. The second, revised group of texts is much larger than the first. Some manuscripts contain parts of the Bible in the earlier version, and other parts in the later version; this suggests that the early version may have been meant as a rough draft that was to be recast into the somewhat better English of the second version. The second version, though somewhat improved, still retained a number of infelicities of style, as in its version of Genesis 1:3

- Latin Vulgate: Dixitque Deus: Fiat lux, et facta est lux

- Early Wyclif: And God said: Be made light, and made is light

- Later Wyclif: And God said: Light be made; and light was made

- King James: And God said: Let there be light; and there was light

The familiar verse of John 3:16 is rendered in the later Wyclif version as:

- For God louede so the world that he yaf his oon bigetun sone, that ech man that beliueth in him perische not, but haue euerlastynge lijf.

The association between Wyclif's Bible and Lollardy caused the kingdom of England and the established Roman Catholic Church to undertake a drastic campaign to suppress it. In the early years of the 15th century, Henry IV (De haeretico comburendo), Archbishop Thomas Arundel, and Henry Knighton (to name a few) published criticism and enacted some of the severest religious censorship laws in Europe at that time. Even twenty years after Wycliffe's death, at the Oxford Convocation of 1408, it was solemnly voted that no new translation of the Bible should be made without prior approval. However, as the text translated in the various versions of the Wyclif Bible was the Latin Vulgate, and as it contained no heterodox readings, there was in practice no way by which the ecclesiastical authorities could distinguish the banned version; and consequently many Catholic commentators of the 15th and 16th centuries (such as Thomas More) took these manuscript English bibles to represent an anonymous earlier orthodox translation. Consequently manuscripts of the Wycliffe Bible, which when inscribed with a date always purport to precede 1409, the date of the ban, circulated freely and were widely used by clergy and laity.

Contents |

Reasons for Translation

When Wycliffe took on the challenge of translating the bible he was breaking a long held belief that no person should translate the Bible on their own initiative, without church approval. His frustrations drove him to ignore this. Wycliffe believed that studying the bible was more important than listening to it read by the clergy. At that time people mainly heard the Bible at church since they did not know how to read and the Bible was costly (before the printing press). He believed every Christian should study the bible. When met with opposition to the translation he replied “Christ and his apostles taught the people in that tongue that was best known to them. Why should men not do so now?” For one to have a personal relationship with God, Wycliffe believed that need to be described in the bible. Wycliff also believed that it was necessary to return to the primitive state of the New Testament in order to truly reform the church. So one must be able to read the bible to understand those times. [] The Bible being in Latin did not work as well in England, unlike many of the other European nations whose language stemmed from Latin (Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French, etc). Eventually the Catholic church did approval an English translation (1582-1610) which was produced by a group of English exiles in good standing with the church.

Two Versions

There are two distinct versions of Wycliffe's Bible that have been written, the earlier was translated during the life of Wycliffe. The later version is regarded as the work of John Purvey. Since the printing press was not invented yet there exists only a very few copies of Wycliffe's earlier bible. The earlier bible is a rigid and literal translation of the Latin Vulgate Bible, Wycliffe's view of theology is close to realism rather than spiritual. This version was translated word for word which often lead to confusion of meaninglessness. It was aimed towards the less learned clergymen and the lay man where as the second more coherent version was aimed towards all literates. It is important to note that after the translations the illiterate and poor lacked the means to the Scripture, the translation originally cost four marks and forty pence. <sup[]</sup> During Wycliffe's time bibles were used as a law-code, which dominated civil law, giving an extreme amount of power to the church and religious leaders who were learned men in Latin. The literal taste of the earlier translation was used to give Wycliffe's Bible an authoritative tone. The earlier version is said to be written by Wycliffe himself and Nicholas of Hereford.

The later revised version of Wycliffe's Bible was issued ten to twelve years after Wycliffe's death. This version is translated by John Purvey, who diligently worked on the translation of Wycliffe's Bible as can be seen in the General Prologue, where Purvey explains the methodology of translating holy scriptures. He describes four rules all translators should acknowledge: Firstly, the translator must be sure of the text he/she is translating. This he has done by comparing many old copies of the Latin bible to assure authenticity of the text. Secondly, the translator must study the text in order to understand the meaning. Purvey explains that one cannot translate a text without having a grasp of what is being read. Third, the translator must consult grammar, diction, and reference works to understand rare and unfamiliar words.Fourth, once the translator understands the text, translation begins by not giving a literal interpretation but expressing the meaning of the text in the receptor language (English) not just translating the word but the sentence as well.<sup[]</sup>

Church reaction and controversy

At this time, the Peasants’ Revolt was running full force as the people of England united to rebel against the unfairness of British Parliament and its favorism of the wealthier classes. William Courtenay, the Archbishop of Canterbury was able to turn both the church and Parliament against Wycliffe by falsely stating that his writings and his influence were fueling the peasants involved in the revolt. (It was actually John Ball, another priest, who was involved in the revolt and merely quoted Wycliffe in one of his speeches.) The Church and Parliament’s anger towards Wycliffe’s “heresy” led them to form The Blackfriars Synod in order to remove Wycliffe from Oxford. Although this Synod was initially delayed by an earthquake that Wycliffe himself believed symbolized “the judgment of God,” it eventually re-convened. At this synod, Wycliffe’s writings (Biblical and otherwise) were quoted and criticized for heresy. This Synod ultimately resulted in King Richard II ruling that Wycliffe be removed from Oxford, and that all who preached or wrote against Catholicism be imprisoned.<sup[]</sup>

References

- 1. Catholic Encyclopedia Versions of the Bible

- 2. Robinson, Henry Wheeler. The Bible in its Ancient and English Versions. Greenwood Press Publishers: Westport, Connecticut. 1970. 137-145.

External links

- Scanned in 1390 Wycliffe Bible

- Studylight version of The Wycliffe Bible (1395) Searchable by phrase or chapter/verse reference.

- John Wyclif; contains a text of the Wycliffite Bible

- John Wycliffe Translation from Wesley NNU; gives each book on a single page

- Vernacular Scriptures before Wycliff

- Catholic Encyclopedia article on John Wyclif

For further reading

- David Daniell, The Bible in English (Yale, 2003); ISBN 0-300-09930-4

- Josiah Forshall and Frederic Madden, eds., The Holy Bible: Wycliffite Versions, 4 vols. (Oxford 1850)