Revelation 16:5

From Textus Receptus

(→Textus Receptus) |

(→Textus Receptus) |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

Dr. John Wordsworth (who edited and footnoted a three volume critical edition of the New Testament in Latin) pointed out that the like phrase in Revelation 1:4 "which is, and which was, and which is to come;" sometimes is rendered in Latin as "qui est et qui fuisti et futurus es" instead of the Vulgate "qui est et qui erat et qui uenturus est." (John Wordsworth, Nouum Testamentum Latine, vol.3, 422 and 424.) | Dr. John Wordsworth (who edited and footnoted a three volume critical edition of the New Testament in Latin) pointed out that the like phrase in Revelation 1:4 "which is, and which was, and which is to come;" sometimes is rendered in Latin as "qui est et qui fuisti et futurus es" instead of the Vulgate "qui est et qui erat et qui uenturus est." (John Wordsworth, Nouum Testamentum Latine, vol.3, 422 and 424.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wordsworth also points out that in Revelation 16:5, Beatus of Liebana (who compiled a commentary on the book of Revelation) uses the Latin phrase "qui fuisti et futures es." This gives some additional evidence for the Greek reading by Beza (although he apparently drew his conclusion for other reasons). Beatus compiled his commentary in 786 AD. Furthermore, Beatus was not writing his own commentary. Instead he was making a compilation and thus preserving the work of Tyconius, who wrote his commentary on Revelation around 380 AD (Aland and Aland, 211 and 216. Altaner, 437. Wordsword, 533.). So, it would seem that as early as 786, and possibly even as early as 380, their was an Old Latin text which read as Beza's Greek text does. | ||

==Other Greek== | ==Other Greek== | ||

Revision as of 11:14, 30 August 2009

Revelation 16:5 And I heard the angel of the waters say, Thou art righteous, O Lord, which art, and wast, and shalt be, because thou hast judged thus.

- 1395 [And the thridde aungel... seide,] Just art thou, Lord, that art, and that were hooli, that demest these thingis; (Wycliffe)

- 1526 And I herde an angell saye: lorde which arte and wast thou arte ryghteous and holy because thou hast geve soche iudgmentes (Tyndale)

- 1535 And I herde an angel saye: LORDE which art and wast, thou art righteous and holy, because thou hast geue soche iudgmentes, (Coverdale)

- 1557 And I heard the Angel of the waters say, Lord, thou art iust, Which art, and Which wast: and Holy, because thou hast iudged these things. (Geneva)

- 1568 And I hearde the angell of the waters say: Lorde, which art, and wast, thou art ryghteous & holy, because thou hast geuen such iudgementes: (Bishop’s)

Contents |

Textus Receptus

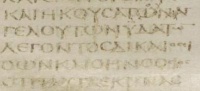

- 1550 καὶ ἤκουσα τοῦ ἀγγέλου τῶν ὑδάτων λέγοντος Δίκαιος Κύριε, εἶ ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἦν καὶ ὁ ὅσιος ὅτι ταῦτα ἔκρινας (Stephanus)

- 1598 καὶ ἤκουσα τοῦ ἀγγέλου τῶν ὑδάτων λέγοντος, Δίκαιος, Κύριε, εἶ ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἦν καὶ ὁ ἐσόμενος, ὅτι ταῦτα ἔκρινας· (Beza)

Beza himself comments on this change in a marginal note of his Greek New Testament:

"And shall be": The usual publication is "holy one," which shows a division, contrary to the whole phrase which is foolish, distorting what is put forth in scripture. The Vulgate, however, whether it is articulately correct or not, is not proper in making the change to "holy," since a section (of the text) has worn away the part after "and," which would be absolutely necessary in connecting "righteous" and "holy one." But with John there remains a completeness where the name of Jehovah (the Lord) is used, just as we have said before, 1:4; he always uses the three closely together, therefore it is certainly "and shall be," for why would he pass over it in this place? And so without doubting the genuine writing in this ancient manuscript, I faithfully restored in the good book what was certainly there, "shall be." So why not truthfully, with good reason, write "which is to come" as before in four other places, namely 1:4 and 8; likewise in 4:3 and 11:17, because the point is the just Christ shall come away from there and bring them into being: in this way he will in fact appear setting in judgment and exercising his just and eternal decrees.

(Theodore Beza, Nouum Sive Nouum Foedus Iesu Christi, 1589. Translated into English from the Latin footnote.)

D. A. Waite says that modern English versions are theologically deficient at Revelation 16:5 for the removal of "and shalt be" (Defending the KJB, p. 170). Waite wrote: “The removal of ‘and shalt be’ puts in doubt the eternal future of the Lord Jesus Christ. This is certainly a matter of doctrine and theology” (p. 170).

Dr. John Wordsworth (who edited and footnoted a three volume critical edition of the New Testament in Latin) pointed out that the like phrase in Revelation 1:4 "which is, and which was, and which is to come;" sometimes is rendered in Latin as "qui est et qui fuisti et futurus es" instead of the Vulgate "qui est et qui erat et qui uenturus est." (John Wordsworth, Nouum Testamentum Latine, vol.3, 422 and 424.)

Wordsworth also points out that in Revelation 16:5, Beatus of Liebana (who compiled a commentary on the book of Revelation) uses the Latin phrase "qui fuisti et futures es." This gives some additional evidence for the Greek reading by Beza (although he apparently drew his conclusion for other reasons). Beatus compiled his commentary in 786 AD. Furthermore, Beatus was not writing his own commentary. Instead he was making a compilation and thus preserving the work of Tyconius, who wrote his commentary on Revelation around 380 AD (Aland and Aland, 211 and 216. Altaner, 437. Wordsword, 533.). So, it would seem that as early as 786, and possibly even as early as 380, their was an Old Latin text which read as Beza's Greek text does.

Other Greek

- καί ἀκούω ὁ ἄγγελος ὁ ὕδωρ λέγω δίκαιος εἰμί ὁ εἰμί καί ὁ εἰμί ὁ ὅσιος ὅτι οὗτος κρίνω Tischendorf 8th Ed

- καὶ ἤκουσα τοῦ ἀγγέλου τῶν ὑδάτων λέγοντος, δίκαιος εἶ, ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἦν ὁ ὅσιος, ὅτι ταῦτα ἔκρινας Westcott / Hort, UBS4

Critical

According to Edward F. Hills, this KJV rendering “shalt be” came from a conjectural emendation interjected into the Greek text by Beza (Believing Bible Study, pp. 205-206). Hills again acknowledged that Theodore Beza introduced a few conjectural emendations in his edition of the Textus Receptus with two of them kept in the KJV, one of them at Revelation 16:5 shalt be instead of holy.

Like Calvin, Beza introduced a few conjectural emendations into his New Testament text. In the providence of God, however, only two of these were perpetuated in the King James Version, namely, Romans 7:6 that being dead wherein instead of being dead to that wherein, and Revelation 16:5 shalt be instead of holy. In the development of the Textus Receptus the influence of the common faith kept conjectural emendation down to a minimum. [1]

Edward Hills identified the KJV reading at Revelation 16:5 as “certainly erroneous” and as a “conjectural emendation by Beza” (Believing Bible Study, p. 83).

William W. Combs maintained: “Beza simply speculated (guessed), without any evidence whatsoever, that the correct reading was ‘shall be’ instead of ‘holy one’” (Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal, Fall, 1999, p. 156).

J. I. Mombert listed Revelation 16:5 as one of the places where he maintained that “the reading of the A. V. is supported by no known Greek manuscript whatever, but rests on an error of Erasmus or Beza” (Hand-book, p. 389).

Bullinger indicated that 1624 edition of the Elzevirs’ Greek text has “the holy one” at this verse (Lexicon, p. 689). In his commentary on the book of Revelation, Walter Scott asserted that the KJV’s rendering “shalt be” was an unnecessary interpolation and that the KJV omitted the title “holy One” (p. 326).

Bruce Metzger defines this term as,

The classical method of textual criticism . . . If the only reading, or each of several variant readings, which the documents of a text supply is impossible or incomprehensible, the editor's only remaining resource is to conjecture what the original reading must have been. A typical emendation involves the removal of an anomaly. It must not be overlooked, however, that though some anomalies are the result of corruption in the transmission of the text, other anomalies may have been either intended or tolerated by the author himself. Before resorting to conjectural emendation, therefore, the critic must be so thoroughly acquainted with the style and thought of his author that he cannot but judge a certain anomaly to be foreign to the author's intention. (Metzger, The Text Of The New Testament, 182.)

References

- 1. Edward F. Hills, The King James Version Defended, p. 208

External Links

- Revelation 16:5 by Will Kinney

- Revelation 16:5

- [1]

- Study Helps