Peshitta

From Textus Receptus

(→History of the Syriac versions) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| - | The '''Peshitta''' ([[Classical Syriac]] (ܦܹܫܝܼܛܵܐ) for "simple, common, straight, [[vulgate]]") is the standard version of the [[ | + | The '''Peshitta''' ([[Classical Syriac]] (ܦܹܫܝܼܛܵܐ) for "simple, common, straight, [[vulgate]]") sometimes called the '''Syriac Vulgate''') is the standard version of the [[Bible]] for churches in the [[Syriac Christianity|Syriac tradition]]. |

The [[Old Testament]] of the Peshitta was translated from the [[Hebrew (language)|Hebrew]], probably in the 2nd century. The [[New Testament]] of the Peshitta, which originally excluded certain disputed books ([[Second Epistle of Peter|2 Peter]], [[Second Epistle of John|2 John]], [[Third Epistle of John|3 John]], [[Epistle of Jude]], [[Book of Revelation|Revelation]]), had become the standard by the early 5th century. | The [[Old Testament]] of the Peshitta was translated from the [[Hebrew (language)|Hebrew]], probably in the 2nd century. The [[New Testament]] of the Peshitta, which originally excluded certain disputed books ([[Second Epistle of Peter|2 Peter]], [[Second Epistle of John|2 John]], [[Third Epistle of John|3 John]], [[Epistle of Jude]], [[Book of Revelation|Revelation]]), had become the standard by the early 5th century. | ||

== The name 'Peshitta' == | == The name 'Peshitta' == | ||

| - | The name 'Peshitta' is derived from the [[Syriac language|Syriac]] ''mappaqtâ pšîṭtâ'' (ܡܦܩܬܐ ܦܫܝܛܬܐ), literally meaning 'simple version'. However, it is also possible to translate ''pšîṭtâ'' as 'common' (that is, for all people), or 'straight', as well as the usual translation as 'simple'. Syriac is a dialect, or group of dialects, of Eastern [[Aramaic language|Aramaic]]. It is written in the [[Syriac alphabet]], and is transliterated into the [[ | + | The name 'Peshitta' is derived from the [[Syriac language|Syriac]] ''mappaqtâ pšîṭtâ'' (ܡܦܩܬܐ ܦܫܝܛܬܐ), literally meaning 'simple version'. However, it is also possible to translate ''pšîṭtâ'' as 'common' (that is, for all people), or 'straight', as well as the usual translation as 'simple'. Syriac is a dialect, or group of dialects, of Eastern [[Aramaic language|Aramaic]], originating in and around [[Assuristan]] ([[Persia]]n ruled [[Assyria]]). It is written in the [[Syriac alphabet]], and is transliterated into the [[Latin script]] in a number of ways: Peshitta, Peshittâ, Pshitta, Pšittâ, Pshitto, Fshitto. All of these are acceptable, but 'Peshitta' is the most conventional spelling in English. |

Its Arabic counterpart is البسيطة "{{unicode|Al-Basîṭah}}", also meaning "The simple [one]". | Its Arabic counterpart is البسيطة "{{unicode|Al-Basîṭah}}", also meaning "The simple [one]". | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

== History of the Syriac versions == | == History of the Syriac versions == | ||

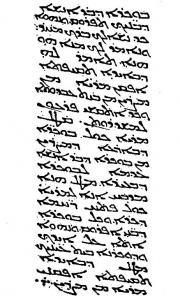

| - | [[Image:Peshitta464.jpg|left|thumb|Peshitta text of [[ | + | [[Image:Peshitta464.jpg|left|thumb|Peshitta text of [[Exodus 13:14]]-[[Exodus 13:16|16]] produced in [[Diyarbakır|Amida]] in the year [[464 AD|464]].]] |

| - | + | === Analogy of Latin Vulgate === | |

| + | We have no full and clear knowledge of the circumstances under which the Peshitta was produced and came into circulation. Whereas the authorship of the [[Latin language|Latin]] [[Vulgate]] has never been in dispute, almost every assertion regarding the authorship of the Peshitta, and the time and place of its origin, is subject to question. The chief ground of analogy between the [[Vulgate]] and the Peshitta is that both came into existence as the result of a revision. This, indeed, has been strenuously denied, but since Dr. Hort in his Introduction to Westcott and Hort's New Testament in the Original Greek, following Griesbach and Hug at the beginning of the 19th century, maintained this view, it has gained many adherents. So far as the Gospels and other [[New Testament]] books are concerned, there is evidence in favor of this view which has been added to by recent discoveries; and fresh investigation in the field of Syriac scholarship has raised it to a high degree of probability. The very designation, "Peshito," has given rise to dispute. It has been applied to the Syriac as the version in common use, and regarded as equivalent to the [[Biblical Greek|Greek koine]] and the Latin Vulgate.<sup>[]</sup> | ||

| - | The Peshitta | + | === The Designation "Peshito" ("Peshitta") === |

| + | The word itself is a [[Grammatical gender|feminine]] form, meaning "simple," "easy to be understood." It seems to have been used to distinguish the version from others which are encumbered with marks and signs in the nature of a [[critical apparatus]]. However this may be, the term as a designation of the version has not been found in any [[Syriac language|Syriac]] author earlier than the 9th or 10th century. | ||

| - | + | As regards the [[Old Testament]], the antiquity of the Version is admitted on all hands. The tradition, however, that part of it was translated from [[Biblical Hebrew|Hebrew]] into [[Classical Syriac|Syriac]] for the benefit of Hiram in the days of Solomon is a myth. That a translation was made by a priest named Assa, or Ezra, whom the king of Assyria sent to Samaria, to instruct the Assyrian colonists mentioned in [[2 Kings]] 17, is equally legendary. That the translation of the Old Testament and New Testament was made in connection with the visit of Thaddaeus to Abgar at Edessa belongs also to unreliable tradition. Mark has even been credited in ancient Syriac tradition with translating his own Gospel (written in Latin, according to this account) and the other books of the New Testament into Syriac.<sup>[1]</sup> | |

| - | + | == Syriac Old Testament == | |

| + | But what [[Theodore of Mopsuestia]] says of the Old Testament is true of both: "These Scriptures were translated into the tongue of the [[Syriacs]] by someone indeed at some time, but who on earth this was has not been made known down to our day".<sup>[2]</sup> [[F. Crawford Burkitt]] concluded that the translation of the Old Testament was probably the work of Jews, of whom there was a colony in [[Edessa, Mesopotamia|Edessa]] about the commencement of the Christian era.<sup>[3]</sup> The older view was that the translators were [[Christians]], and that the work was done late in the 1st century or early in the 2nd. The Old Testament known to the early Syrian church was substantially that of the [[Palestinian Jews]]. It contained the same number of books but it arranged them in a different order. First there was the [[Pentateuch]], then [[Book of Job|Job]], [[Joshua]], [[Book of Judges|Judges]], 1 and 2 [[Samuel]], 1 and 2 [[Books of Kings|Kings]], 1 and 2 [[Books of Chronicles|Chronicles]], [[Psalms]], [[Book of Proverbs|Proverbs]], [[Ecclesiastes]], [[Book of Ruth|Ruth]], [[Canticles]], [[Esther]], [[Ezra]], [[Nehemiah]], [[Isaiah]] followed by the Twelve [[Minor Prophets]], [[Jeremiah]] and [[Book of Lamentations|Lamentations]], [[Ezekiel]], and lastly [[Daniel]]. Most of the [[Old Testament Apocrypha|apocryphal books of the Old Testament]] are found in the Syriac, and the [[Wisdom of Sirach]] is held to have been translated from the [[Hebrew]] and not from the [[Septuagint]].<sup>[1]</sup> | ||

| - | + | == Syriac New Testament == | |

| + | Of the New Testament, attempts at translation must have been made very early, and among the ancient versions of New Testament Scripture the Syriac in all likelihood is the earliest. It was at [[Antioch]], the capital of [[Syria (Roman province)|Syria]], that the disciples of Christ were first called [[Christian]]s, and it seemed natural that the first translation of the Christian Scriptures should have been made there. Some research, however, goes to show that [[Edessa]], the literary capital, could have been the place. | ||

| - | + | If we could accept the somewhat obscure statement of [[Eusebius]]<sup>[4]</sup> that [[Hegesippus (chronicler)|Hegesippus]] "made some quotations from the Gospel according to the Hebrews and from the Syriac Gospel," we should have a reference to a Syriac New Testament as early as 160-80 AD, the time of that Hebrew Christian writer. One thing is certain, that the earliest New Testament of the Syriac church lacked not only the [[Antilegomena]] – 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, Jude, and [[Book of Revelation|the Apocalypse]] – but the whole of the [[Catholic Epistles]]. These were at a later date translated and received into the Syriac Canon of the New Testament, but the quotations of the early Syrian Fathers take no notice of these New Testament books. | |

| + | |||

| + | From the 5th century, however, the Peshitta containing both Old Testament and New Testament has been used in its present form only as the national version of the Syriac Scriptures. The translation of the New Testament is careful, faithful and literal, and the simplicity, directness and transparency of the style are admired by all Syriac scholars and have earned for it the title of "Queen of the versions." <sup>[1]</sup> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Old Syriac texts == | ||

| + | It is in the Gospels, however, that the analogy between the [[Latin Vulgate]] and the Syriac Vulgate can be established by evidence. If the Peshitta is the result of a revision as the Vulgate was, then we may expect to find Old Syriac texts answering to the [[Vetus Latina|Old Latin]]. Such texts have actually been found. Three such texts have been recovered, all showing divergences from the Peshitta, and believed by competent scholars to be anterior to it. These are, to take them in the order of their recovery in modern times, (1) the Curetonian Syriac, (2) the Syriac of Tatian's Diatessaron, and (3) the Sinaitic Syriac.<p>[1]</sup> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Details on Curetonian | ||

| + | The Curetonian consists of fragments of the Gospels brought in [[1842 AD|1842]] from the Nitrian Desert in Egypt and now in the [[British Museum]]. The fragments were examined by Canon Cureton of Westminster and edited by him in [[1858 AD|1858]]. The manuscript from which the fragments have come appears to belong to the 5th century, but scholars believe the text itself to be as old as the 100's AD. In this recension the Gospel according to Matthew has the title Evangelion da-Mepharreshe, which will be explained in the next section. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Details on Tatian's ''Diatessaron'' | ||

| + | The ''[[Diatessaron]]'' of [[Tatian]] is the work which Eusebius ascribes to that heretic, calling it that "combination and collection of the Gospels, I know not how, to which he gave the title Diatessaron." It is the earliest harmony of the Four Gospels known to us. Its existence is amply attested in the churches of Mesopotamia and Syria, but it had disappeared for centuries, and not a single copy of the Syriac work survives. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A commentary upon it by Ephraem the Syrian, surviving in an [[Armenian language|Armenian]] translation, was issued by the Mechitarist Fathers at Venice in [[1836 AD|1836]], and afterward translated into Latin. Since [[1876 AD|1876]] an Arabic translation of the Diatessaron itself has been discovered; and it has been ascertained that the Cod. Fuldensis of the Vulgate represents the order and contents of the Diatessaron. A translation from the Arabic can now be read in English in Dr. J. Hamlyn Hill's The Earliest Life of Christ Ever Compiled from the Four Gospels. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although no copy of the Diatessaron has survived, the general features of Tatian's Syriac work can be gathered from these materials. It is still a matter of dispute whether Tatian composed his Harmony out of a Syriac version already made, or composed it first in Greek and then translated it into Syriac. But the existence and widespread use of a Harmony, combining in one all four Gospels, from such an early period ([[172 AD]]), enables us to understand the title Evangelion da-Mepharreshe. It means "the Gospel of the Separated," and points to the existence of single Gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, in a Syriac translation, in contradistinction to Tatian's Harmony. Theodoret, bishop of Cyrrhus in the 5th century, tells how he found more than 200 copies of the Diatessaron held in honor in his diocese and how he collected them, and put them out of the way, associated as they were with the name of a heretic, and substituted for them the Gospels of the four evangelists in their separate forms. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Sinaitic Syriac | ||

| + | In [[1892 AD|1892]] the discovery of the third text, known, from the place where it was found, as the [[Syriac Sinaiticus|Sinaitic Syriac]], comprising the four Gospels nearly entire, heightened the interest in the subject and increased the available material. It is a palimpsest, and was found in the monastery of Catherine on Mt. Sinai by Mrs. Agnes S. Lewis and her sister Mrs. Margaret D. Gibson. The text has been carefully examined and many scholars regard it as representing the earliest translation into Syriac, and reaching back into the 2nd century. Like the Curetonian, it is an example of the Evangelion da-Mepharreshe as distinguished from the Harmony of Tatian. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Relation to Peshitta | ||

| + | The discovery of these texts has raised many questions which it may require further discovery and further investigation to answer satisfactorily. It is natural to ask what is the relation of these three texts to the Peshitta. There are still scholars, foremost of whom is G. H. Gwilliam, the learned editor of the Oxford Peshito,<sup>[5]</sup> who maintain the priority of the Peshitta and insist upon its claim to be the earliest monument of Syrian Christianity. But the progress of investigation into Syriac Christian literature points distinctly the other way. From an exhaustive study of the quotations in the earliest Syriac Fathers, and, in particular, of the works of Ephraem Syrus, Professor Burkitt concludes that the Peshitta did not exist in the 4th century. He finds that Ephraem used the Diatessaron in the main as the source of his quotation, although "his voluminous writings contain some clear indications that he was aware of the existence of the separate Gospels, and he seems occasionally to have quoted from them.<sup>[6]</sup> Such quotations as are found in other extant remains of Syriac literature before the 5th century bear a greater resemblance to the readings of the Curetonian and the Sinaitic than to the readings of the Peshitta. Internal and external evidence alike point to the later and revised character of the Peshitta. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Brief History of the Peshitta == | ||

| + | The Peshitta had from the 5th century onward a wide circulation in the East, and was accepted and honored by all the numerous sects of the greatly divided Syriac Christianity. It had a great missionary influence, and the Armenian and Georgian versions, as well as the Arabic and the Persian, owe not a little to the Syriac. The famous Nestorian tablet of Sing-an-fu witnesses to the presence of the Syriac Scriptures in the heart of China in the 7th century. It was first brought to the West by Moses of Mindin, a noted Syrian ecclesiastic, who sought a patron for the work of printing it in vain in Rome and Venice, but found one in the Imperial Chancellor at Vienna in [[1555 AD|1555]]—Albert Widmanstadt. He undertook the printing of the New Testament, and the emperor bore the cost of the special types which had to be cast for its issue in Syriac. Immanuel Tremellius, the converted Jew whose scholarship was so valuable to the English reformers and divines, made use of it, and in [[1569 AD|1569]] issued a Syriac New Testament in Hebrew letters. In [[1645 AD|1645]] the editio princeps of the Old Testament was prepared by Gabriel Sionita for the Paris Polyglot, and in [[1657 AD|1657]] the whole Peshitta found a place in Walton's ''[[London Polyglot]]''. For long the best edition of the Peshitta was that of John Leusden and Karl Schaaf, and it is still quoted under the symbol Syrschaaf, or SyrSch. The critical edition of the Gospels recently issued by Mr. G. H. Gwilliam at the Clarendon Press is based upon some 50 manuscripts. Considering the revival of Syriac scholarship, and the large company of workers engaged in this field, we may expect further contributions of a similar character to a new and complete critical edition of the Peshitta.<sup>[1]</sup> | ||

== Old Testament Peshitta == | == Old Testament Peshitta == | ||

| - | [[ | + | [[Image:TextsOT.PNG|thumb|right|350px|The inter-relationship between various significant ancient manuscripts of the Old Testament (some identified by their siglum). [[LXX]] here denotes the original septuagint.]] |

| - | The Peshitta version of the Old Testament is an independent translation based largely on a Hebrew text similar to the [[Proto-Masoretic]] Text. It shows a number of linguistic and exegetical similarities to the Aramaic Targums but is now no longer thought to derive from them. In some passages the translators have | + | The Peshitta version of the Old Testament is an independent translation based largely on a Hebrew text similar to the [[Proto-Masoretic]] Text. It shows a number of linguistic and exegetical similarities to the Aramaic Targums but is now no longer thought to derive from them. In some passages the translators have may have used the Greek [[Septuagint]]. The influence of the Septuagint is particularly strong in [[Isaiah]] and the [[Psalms]], probably due to their use in the liturgy. Most of the [[Deuterocanonicals]] are translated from the [[Septuagint]], and the translation of [[Wisdom of Sirach|Sirach]] was based on a Hebrew text. |

| - | The choice of books included in the Old Testament Peshitta changes from one manuscript to another. Usually most of the | + | The choice of books included in the Old Testament Peshitta changes from one manuscript to another. Usually most of the Deuterocanonicals are present. Other [[Biblical apocrypha]]s, as [[1 Esdras]], [[3 Maccabees]], [[4 Maccabees]], [[Psalm 151]] can be found in some manuscripts. The manuscript of [[Biblioteca Ambrosiana]], discovered in [[1866 AD|1866]], includes also [[2 Baruch]] (''Syriac Apocalypse of Baruch''). |

| - | === Main | + | === Main manuscripts === |

More than 250 manuscripts of the Old Testament Peshitta are known, and the main and older ones are: | More than 250 manuscripts of the Old Testament Peshitta are known, and the main and older ones are: | ||

| - | * ''[[London]], [[British Library]], Add. 14,425'' (also referred to as "5b1" in Leiden numeration): dated in the second half of | + | * ''[[London]], [[British Library]], Add. 14,425'' (also referred to as "5b1" in Leiden numeration): dated in the second half of 5th century, it includes only [[Book of Genesis|Genesis]], [[Book of Exodus|Exodus]], [[Book of Numbers|Numbers]] and [[Deuteronomy]]. The text is more similar to the [[Masoretic Text]] than the text of most other manuscripts, even if somewhere it has relevant differences. |

| - | * ''[[Milan]], [[Biblioteca Ambrosiana]], B. 21 inf'' (also referred to as "7a1"): it was discovered by [[Antonio Ceriani]] in 1866 and published in 1876-1883. This manuscript dates from the sixth or the | + | * ''[[Milan]], [[Biblioteca Ambrosiana]], B. 21 inf'' (also referred to as "7a1"): it was discovered by [[Antonio Ceriani]] in [[1866 AD|1866]] and published in [[1876 AD|1876]]-[[1883 AD|1883]]. This manuscript dates from the sixth or the 7th century. In [[1006 AD|1006]]/[[1007 AD|7]] it became part of the library of the [[Syrian Monastery]] in [[Egypt]] and in the 17th century was moved to Milan. The text is used as base text in the critical edition of Peshitta Institute of Leiden. It includes all the books of the [[Hebrew Bible]] and [[Wisdom (of Solomon)]], [[Letter of Jeremiah]], [[Book of Baruch|Baruch]], [[Bel and the Dragon]], [[Book of Susanna|Susanna]], [[Book of Judith|Judith]], [[Wisdom of Sirach|Sirach]], [[1 Maccabees]], [[2 Maccabees]], [[3 Maccabees]], [[4 Maccabees]], [[2 Baruch]] (the only extant manuscript in Syriac) with the [[Letter of Baruch]], [[2 Esdras]], and the second book of [[The Jewish War]]<sup>[7]</sup> |

| - | > | + | * ''[[Paris]], [[Bibliothèque National]], Syr. 341'' (also referred to as "8a1"): it dates from the eight century or even before and has many corrections. It includes all the books of the [[Hebrew Bible]] and [[Wisdom (of Solomon)]], [[Letter of Jeremiah]], [[Book of Baruch|Baruch]], [[Bel and the Dragon]], [[Book of Susanna|Susanna]], [[Book of Judith|Judith]], [[Wisdom of Sirach|Sirach]], [[1 Maccabees]], [[2 Maccabees]], [[3 Maccabees]], [[Book of Odes (Bible)|Odes]], [[Prayer of Manasseh]], [[Letter of Baruch]]<sup>[7]</sup> |

| - | * ''[[Paris]], [[Bibliothèque National]], Syr. 341'' (also referred to as "8a1"): it dates from the eight century or even before and has many corrections. It includes all the books of the [[Hebrew Bible]] and [[Wisdom (of Solomon)]], [[Letter of Jeremiah]], [[Book of Baruch|Baruch]], [[Bel and the Dragon]], [[Book of Susanna|Susanna]], [[Book of Judith|Judith]], [[Sirach]], [[1 Maccabees]], [[2 Maccabees]], [[3 Maccabees]], [[Book of Odes (Bible)|Odes]], [[Prayer of Manasseh]], [[Letter of Baruch]]<sup>[]</sup> | + | * ''[[Florence]], [[Laurentian Library]], Or. 58'' (also referred to as "9a1"): this manuscript has a text more similar to the [[Masoretic Text]] as "5b1" has, and scholars don't know if this is due to a more original text, or to later corrections. It includes all the books of the [[Hebrew Bible]] and [[Bel and the Dragon]], [[Book of Susanna|Susanna]], [[Book of Judith|Judith]], [[Prayer of Manasseh]]<sup>[7]</sup> |

| - | * ''[[Florence]], [[Laurentian Library]], Or. 58'' (also referred to as "9a1"): this manuscript has a text more similar to the [[Masoretic Text]] as "5b1" has, and scholars don't know if this is due to a more original text, or to later corrections. It includes all the books of the [[Hebrew Bible]] and [[Bel and the Dragon]], [[Book of Susanna|Susanna]], [[Book of Judith|Judith]], [[Prayer of Manasseh]]< | + | * ''[[Cambridge]], [[Cambridge University Library|University Library]], Oo.I.1,2'' (also referred to as "12a1" or as "''[[Claudius Buchanan|Buchanan]] Bible''"): it is a 12th century manuscript that probably originated in [[Tur Abdin]] area, and was later moved to [[India]] and later to Cambridge by [[Claudius Buchanan]] in the early 19th century. It is the best testimony of an important textual family. It includes all the books of the [[Hebrew Bible]] and [[Wisdom (of Solomon)]], [[Letter of Jeremiah]], [[Book of Baruch|Baruch]], [[Bel and the Dragon]], [[Book of Susanna|Susanna]], [[Book of Judith|Judith]], [[Wisdom of Sirach|Sirach]], [[1 Maccabees]], [[2 Maccabees]], [[Book of Tobit|Tobit]], [[3 Maccabees]], [[4 Maccabees]], [[1 Esdras]], [[Letter of Baruch]]<sup>[7]</sup> |

| - | * ''[[Cambridge]], [[Cambridge University Library|University Library]], Oo.I.1,2'' (also referred to as "12a1" or as "''[[Claudius Buchanan|Buchanan]] Bible''"): it is a 12th century manuscript that probably originated in [[Tur Abdin]] area, and was later moved to [[India]] and later to Cambridge by [[Claudius Buchanan]] in the early 19th century. It is the best testimony of an important textual family. It includes all the books of the [[Hebrew Bible]] and [[Wisdom (of Solomon)]], [[Letter of Jeremiah]], [[Book of Baruch|Baruch]], [[Bel and the Dragon]], [[Book of Susanna|Susanna]], [[Book of Judith|Judith]], [[Sirach]], [[1 Maccabees]], [[2 Maccabees]], [[Book of Tobit|Tobit]], [[3 Maccabees]], [[4 Maccabees]], [[1 Esdras]], [[Letter of Baruch]]<sup>[]</sup> | + | |

* ''[[Baghdad]], Library of [[Chaldean Catholic Church|Chaldean]] Patriarchate, 211 (Mosul cod. 4)'': 12th century manuscript used often as base text for [[Psalms 152–155]] | * ''[[Baghdad]], Library of [[Chaldean Catholic Church|Chaldean]] Patriarchate, 211 (Mosul cod. 4)'': 12th century manuscript used often as base text for [[Psalms 152–155]] | ||

| - | === Early | + | === Early print editions === |

| - | * [[Polyglot (book)#Paris Polyglot|Paris Polyglot]], 1645, edited by [[Gabriel Sionita]] and probably based on manuscript "17a5", considered today a recent and not reliable manuscript. | + | * [[Polyglot (book)#Paris Polyglot|Paris Polyglot]], [[1645 AD|1645]], edited by [[Gabriel Sionita]] and probably based on manuscript "17a5", considered today a recent and not reliable manuscript. |

| - | * [[Polyglot (book)#London Polyglot|London Polyglot]], 1657, based on the ''Paris Polyglot'' text with an appendix of the some collations from other manuscripts kept in [[Oxford]] ranging form the 12th to the 17th century. | + | * [[Polyglot (book)#London Polyglot|London Polyglot]], [[1657 AD|1657]], based on the ''Paris Polyglot'' text with an appendix of the some collations from other manuscripts kept in [[Oxford]] ranging form the 12th to the 17th century. |

| - | * [[Samuel Lee (linguist)|Samuel Lee]] edition, first printed in [[London]] in 1823 by the [[British and Foreign Bible Society]] and reprinted in 1826. The text is almost like the ''London Polyglot'''s one. In the 1826 the ''British and Foreign Bible Society'' decided to cut from each printed copy of this Bible the page containing the [[Psalm 151]] because this Psalm is not in the [[Protestant]] [[Biblical canon|canon]]<sup>[]</sup> | + | * [[Samuel Lee (linguist)|Samuel Lee]] edition, first printed in [[London]] in [[1823 AD|1823]] by the [[British and Foreign Bible Society]] and reprinted in [[1826 AD|1826]]. The text is almost like the ''London Polyglot'''s one. In the [[1826 AD|1826]] the ''British and Foreign Bible Society'' decided to cut from each printed copy of this Bible the page containing the [[Psalm 151]] because this Psalm is not in the [[Protestant]] [[Biblical canon|canon]].<sup>[8]</sup> |

| - | * [[Lake Urmia|Urmia]] Bible, published in 1852 by [[Justin Perkins]], that included also a parallel translation in the Urmian dialect of [[Assyrian Neo-Aramaic]] language. | + | * [[Lake Urmia|Urmia]] Bible, published in [[1852 AD|1852]] by [[Justin Perkins]], that included also a parallel translation in the Urmian dialect of [[Assyrian Neo-Aramaic]] language. |

| - | * [[Mosul]] edition, published in 1888-1892 by ''Clement Joseph David'' <sup>[]</sup> and by [[Audishu V Khayyath|Mar Georges Ebed-Iesu Khayyath]] for the [[Dominican Order|Dominican]] mission. This edition, differently from previously editions, includes also some books not in the [[Hebrew Bible]] but found in many Peshitta manuscripts: these books included are: [[Book of Tobit|Tobit]], [[Book of Judith|Judith]], [[ | + | * [[Mosul]] edition, published in [[1888 AD|1888]]-[[1892 AD|1892]] by ''Clement Joseph David'' <sup>[9]</sup> and by [[Audishu V Khayyath|Mar Georges Ebed-Iesu Khayyath]] for the [[Dominican Order|Dominican]] mission. This edition, differently from previously editions, includes also some books not in the [[Hebrew Bible]] but found in many Peshitta manuscripts: these books included are: [[Book of Tobit|Tobit]], [[Book of Judith|Judith]], [[Additions to Esther]], [[Wisdom (of Solomon)]], [[Sirach]], [[Letter of Jeremiah]], [[Book of Baruch|Baruch]], [[Bel and the Dragon]], [[Book of Susanna|Susanna]], [[1 Maccabees]], [[2 Maccabees]], [[2 Baruch]] with the [[Letter of Baruch]]. |

== New Testament Peshitta == | == New Testament Peshitta == | ||

| - | The Peshitta version of the New Testament is thought to show a continuation of the tradition of the Diatessaron and Old Syriac versions, displaying some lively 'Western' renderings (particularly clear in the Acts of the Apostles). It combines with this some of the more complex [[Byzantine text-type|'Byzantine']] readings of the | + | The Peshitta version of the New Testament is thought to show a continuation of the tradition of the Diatessaron and Old Syriac versions, displaying some lively 'Western' renderings (particularly clear in the Acts of the Apostles). It combines with this some of the more complex [[Byzantine text-type|'Byzantine']] readings of the 5th century. One unusual feature of the Peshitta is the absence of [[2 Peter]], [[2 John]], [[3 John]], [[Epistle of Jude|Jude]] and [[Book of Revelation|Revelation]]. Modern Syriac Bibles add 6th or 7th century translations of these five books to a revised Peshitta text. |

| - | Almost all Syriac scholars agree that the Peshitta gospels are translations of the Greek originals. A minority viewpoint (see [[Aramaic primacy]]) is that the Peshitta represent the original New Testament and the Greek is a translation of it. The type of text represented by Peshitta is the [[Byzantine text-type|Byzantine]]. In a detailed examination of Matthew 1-14 Gwilliam found that the Peshitta agrees with the [[Textus Receptus]] only 108 times and with [[Codex Vaticanus]] 65 times, while in 137 instances it differs from both, usually with the support of the Old Syriac and the Old Latin, in 31 instances is stands alone.<sup>[]</sup> | + | Almost all Syriac scholars agree that the Peshitta gospels are translations of the Greek originals. A minority viewpoint (see [[Aramaic primacy]]) is that the Peshitta represent the original New Testament and the Greek is a translation of it. The type of text represented by Peshitta is the [[Byzantine text-type|Byzantine]]. In a detailed examination of Matthew 1-14, Gwilliam found that the Peshitta agrees with the [[Textus Receptus]] only 108 times and with [[Codex Vaticanus]] 65 times, while in 137 instances it differs from both, usually with the support of the Old Syriac and the Old Latin, in 31 instances is stands alone.<sup>[10]</sup> |

In reference to the originality of the Peshitta, the words of Patriarch [[Mar Eshai Shimun XXIII]] are summarized as follows: | In reference to the originality of the Peshitta, the words of Patriarch [[Mar Eshai Shimun XXIII]] are summarized as follows: | ||

| - | :''"With reference to....the originality of the Peshitta text, as the Patriarch and Head of the Holy Apostolic and Catholic Church of the East, we wish to state, that the Church of the East received the scriptures from the hands of the blessed Apostles themselves in the Aramaic original, the language spoken by our Lord Jesus Christ Himself, and that the Peshitta is the text of the Church of the East which has come down from the Biblical times without any change or revision."''< | + | :''"With reference to....the originality of the Peshitta text, as the Patriarch and Head of the Holy Apostolic and Catholic Church of the East, we wish to state, that the Church of the East received the scriptures from the hands of the blessed Apostles themselves in the Aramaic original, the language spoken by our Lord Jesus Christ Himself, and that the Peshitta is the text of the Church of the East which has come down from the Biblical times without any change or revision."''<sup>[11]</sup> |

| - | For more information, see [[Aramaic | + | For more information, see [[Aramaic New Testament]]. |

| - | == | + | ==Critical edition of the New Testament== |

| - | The | + | The standard [[United Bible Societies]] [[1905 AD|1905]] edition of the New Testament of the Peshitta was based on editions prepared by Syriacists [[Philip E. Pusey]] (d.[[1880 AD|1880]]), [[George Gwilliam]] (d.[[1914 AD|1914]]) and [[John Gwyn]].<sup>[12]</sup> These editions comprised Gwilliam & Pusey's 1901 critical edition of the Gospels, Gwilliam's critical edition of Acts, Gwilliam & Pinkerton's critical edition of Paul's Epistles and John Gwynn's critical edition of the General Epistles and later Revelation. This critical Peshitta text is based on a collation of more than seventy Peshitta and a few other Aramaic manuscripts. All twenty seven books of the common western [[canon of the New Testament]] are included in this British & Foreign Bible Society's [[1905 AD|1905]] Peshitta edition, as is the [[adultery pericope]] ([[John 7:53|John 7:53]]-[[John 8:11|8:11]]). The [[1979 AD|1979]] Syriac Bible, United Bible Society, uses the same text for its New Testament. The [[Online Bible]] reproduces the [[1905 AD|1905]] Syriac Peshitta NT in Hebrew characters. |

| - | [[ | + | ==Translations of the Peshitta== |

| + | Both [[John Wesley Etheridge]] ([[1846 AD|1846]]–[[1849 AD|1849]]) and James Murdock ([[1852 AD|1852]])<sup>[13]</sup> produced translations of the New Testament Peshitta in the 19th century. More recently various versions of the New Testament only have appeared arguing this view in the notes. These include: | ||

| + | * [[George M. Lamsa]]- ''The Holy Bible From the Ancient Eastern Text'' ([[1933 AD|1933]])- The only complete English work of both the Old and New Testaments according to the Peshitta text. Lamsa was a native [[Syriac]] speaker. This work is better known as the [[Lamsa Bible]]. He also wrote several other books on the Peshitta and Aramaic Primacy such as ''Gospel Light'', ''New Testament Origin'', and ''Idioms of the Bible'', along with a New Testament commentary. Several well-known evangelists used or endorsed the Lamsa Bible, such as [[Oral Roberts]], [[Billy Graham]], and [[William M. Branham]]. Is not accepted as a translation by formal academics and translators, because Lamsa mixed their very personal nationalist and esoteric Assyrian concepts enclosed on bible text, therefore, is not a serious bible translation but a personal mixed narrative of bible verses, esoteric concepts and wrong doctrine with extra-biblical elements. | ||

| + | * Andrew Gabriel Roth- ''Aramaic English New Testament'' (AENT), which includes a literal translation of the Peshitta on the left side pages with the Aramaic text in Hebrew letters on the right side with Roth's commentary. The AENT is basically a revision of the Younan Interlinear New Testament (from [[Matthew 1]] to [[Acts 15]]) and the James Murdock's ([[Acts 15]] and onward). <sup>[14]</sup> | ||

| + | * Janet Magiera- ''Aramaic Peshitta New Testament Translation'', ''Aramaic Peshitta New Testament Translation- Messianic Version'', and ''Aramaic Peshitta Vertical Interlinear'' (in three volumes). Magiera was an associate of [[George Lamsa]]. | ||

| + | * Reverend Glenn David Bauscher- ''The Aramaic-English Interlinear New Testament'' (1st edition [[2006 AD|2006]]), Psalms, Proverbs & Ecclesiastes (4th edition [[2011 AD|2011]]) <sup>[15]</sup> the basis for ''The Original Aramaic New Testament in Plain English'' ([[2007 AD|2007]], 6th edition [[2011 AD|2011]]). Another literal translation that comes as an interlinear New Testament (with Hebrew characters), and a smoother English version. Bauscher translated from the Western Peshitto text.<sup>[16]</sup> | ||

| + | * Victor Alexander- ''Aramaic New Testament'' and ''Disciples New Testament''. Alexander is a native speaker of Syriac. | ||

| + | * The Way International- ''The Aramaic Interlinear Bible'' | ||

| + | * Paul Younan, a native Syriac speaker, is currently working on an interlinear translation of the Peshitta into English. | ||

| + | * Arch-corepiscopos Curien Kaniamparambil- ''Vishudhagrandham'' Peshitta translation (including Old and New Testaments) in [[Malayalam]], the language of [[Kerala]]. | ||

| + | In Spanish exists [http://www.bhpublishinggroup.com/espanol/products.asp?p=9789704100001 Biblia Peshitta en Español (Spanish Peshitta Bible)] by Holman Bible Publishers, Nashville, TN. U. S. A., published [[2007 AD|2007]]. | ||

| - | + | ==Manuscripts of the New Testament== | |

| + | The following manuscripts are in the British Archives. | ||

| - | + | * [[British Library, Add. 14470]] – complete text of 22 books, from the 5th/6th century | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | * [[British Library, Add. 14470]] | + | |

* [[Rabbula Gospels]] | * [[Rabbula Gospels]] | ||

* [[Khaboris Codex]] | * [[Khaboris Codex]] | ||

| Line 89: | Line 117: | ||

* [[British Library, Add. 14467]] | * [[British Library, Add. 14467]] | ||

* [[British Library, Add. 14669]] | * [[British Library, Add. 14669]] | ||

| - | + | About [[1963 AD|1963]], Mr. Lamsa finally found a publisher for his (Translation), World Bible Publishers, New York. The (relationship) was short-lived, however..and again, Mr. Lamsa went looking for a Publisher. | |

| - | + | In 1966, Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association agreed to use their printing presses to resume (the task). At that time, Vernon Hale was Editor and his wife still possesses the First (signed-dedicated copy), along with a few other gifts from Mr. Lamsa. Formal academics and translators of Peshitta text have revealed that Lamsa's work is not a serious translation, but a personal narrative mixed with esoteric and nationalist Assyrian concepts. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| + | * 1. [http://www.bible-researcher.com/syriac-isbe.html Syriac Versions of the Bible by Thomas Nicol] | ||

| + | * 2. [[Eberhard Nestle]] in [[Hastings' Dictionary of the Bible]], IV, 645b. | ||

| + | * 3. Francis Crawford Burkitt, [http://books.google.com/books?id=vssdKNm9Hm4C&printsec=frontcover&dq=Early+Eastern+Christianity&hl=en&ei=UYLZTZz7CMa08QPHnbGUAg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCkQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=edessa&f=false Early Eastern Christianity], 71 ff. 1904. | ||

| + | * 4. [[Church History (Eusebius)|Historia Ecclesiastica]], IV, xxii | ||

| + | * 5. Tetraevangelium sanctum, Clarendon Press, 1901 | ||

| + | * 6. Evangelion da-Mepharreshe, 186. | ||

| + | * 7. For the order of the books see S. Brock, The Bible in the Syriac Tradition ISBN 1-59333-300-5 p. 116 | ||

| + | * 8. A. S. van der Woude In Quest of the Past ISBN 90-04-09192-0 (1988), p. 70 | ||

| + | * 9. [[Syriac Catholic Church|Syriac Catholic]] Archbishop of [[Damascus]], born [[1829 AD|1829]] | ||

| + | * 10. [[Bruce M. Metzger]], The Early Versions of the New Testament: Their Origin, Transmission and Limitations (Oxford University Press 1977), p. 50. | ||

| + | * 11. His Holiness Mar Eshai Shimun, Catholicos Patriarch of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Church of the East. April 5, 1957 | ||

| + | * 12. Corpus scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium: Subsidia Catholic University of America, 1987 "37 ff. The project was founded by Philip E. Pusey who started the collation work in 1872. However, he could not see it to completion since he died in 1880. Gwilliam, | ||

| + | * 13. [http://books.google.com.au/books?id=gOE2GjKIe1IC&pg=PA5&source=gbs_selected_pages&cad=0_0 The New Testament of the Book of the Holy Gospel of our Lord and our God Jesus the Messiah a Literal Translation from the Syriac Peshito Version.] | ||

| + | * 14. Andrew Gabriel Roth, Aramaic English New Testament, Netzari Press, Third Edition (2010), ISBN 1-934916-26-9 - included all twenty-seven books of the Aramaic New Testament, as a literal translation of the very oldest known Aramaic New Testament texts. This is a study Bible with over 1700 footnotes and 350 pages of appendixes to help the reader understand the poetry, idioms, terms and definitions in the language of Y'shua (Jesus) and his followers. The Aramaic is featured with Hebrew letters and vowel pointing. | ||

| + | * 15. The Aramaic-English Interlinear New Testament 4th edition 2011 | ||

| + | * 16. The Original Aramaic New Testament in Plain English, 6th edition 2011 has also Psalms & Proverbs in plain English from his Peshitta interlinear of those Peshitta Old Testament books, according to [[Codex Ambrosianus]] (6th century?) and Lee's 1816 edition of the Peshitta Old Testament. Bauscher has also published an ''Aramaic-English & English Aramaic Dictionary'' & nine other books related to the Peshitta Bible. The interlinear displays the Aramaic in Ashuri (square Hebrew) letters. | ||

==Sources== | ==Sources== | ||

| Line 104: | Line 143: | ||

* Dirksen, P. B. (1993). ''La Peshitta dell'Antico Testamento'', Brescia, ISBN 88-394-0494-5 | * Dirksen, P. B. (1993). ''La Peshitta dell'Antico Testamento'', Brescia, ISBN 88-394-0494-5 | ||

* Flesher, P. V. M. (ed.) (1998). ''Targum Studies Volume Two: Targum and Peshitta''. Atlanta. | * Flesher, P. V. M. (ed.) (1998). ''Targum Studies Volume Two: Targum and Peshitta''. Atlanta. | ||

| - | * Kiraz, George Anton (1996). ''Comparative Edition of the Syriac Gospels: Aligning the Old Syriac Sinaiticus, Curetonianus, Peshitta and Harklean Versions''. Brill: Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2002 [2nd ed.], 2004 [3rd ed.]. | + | * [[George Kiraz|Kiraz, George Anton]] (1996). ''Comparative Edition of the Syriac Gospels: Aligning the Old Syriac Sinaiticus, Curetonianus, Peshitta and Harklean Versions''. Brill: Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2002 [2nd ed.], 2004 [3rd ed.]. |

| - | * Lamsa, George M. (1933). ''The Holy Bible from Ancient Eastern Manuscripts''. ISBN 0-06-064923-2. | + | * [[George Lamsa|Lamsa, George M.]] (1933). ''The Holy Bible from Ancient Eastern Manuscripts''. ISBN 0-06-064923-2. |

* Pinkerton, J. and R. Kilgour (1920). ''The New Testament in Syriac''. London: British and Foreign Bible Society, Oxford University Press. | * Pinkerton, J. and R. Kilgour (1920). ''The New Testament in Syriac''. London: British and Foreign Bible Society, Oxford University Press. | ||

* Pusey, Philip E. and G. H. Gwilliam (1901). ''Tetraevangelium Sanctum iuxta simplicem Syrorum versionem''. Oxford University Press. | * Pusey, Philip E. and G. H. Gwilliam (1901). ''Tetraevangelium Sanctum iuxta simplicem Syrorum versionem''. Oxford University Press. | ||

* Weitzman, M. P. (1999). ''The Syriac Version of the Old Testament: An Introduction''. ISBN 0-521-63288-9. | * Weitzman, M. P. (1999). ''The Syriac Version of the Old Testament: An Introduction''. ISBN 0-521-63288-9. | ||

| - | + | ;Attribution | |

| + | * Nicol, Thomas. "Syriac Versions" in (1915) ''International Standard Bible Encyclopedia'' | ||

| - | * [http://www. | + | ==See also== |

| - | * [http:// | + | * [[Agnes and Margaret Smith]] |

| - | * [http://www. | + | |

| - | * [http://www.ntcanon.org/Peshitta.shtml The Development of the Canon of the New Testament] | + | == External links == |

| - | * [http://jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=1035&letter=B Jewish Encyclopedia: Bible Translations] | + | * [http://www.dukhrana.com/peshitta/ Dukhrana Biblical Research] |

| - | * [http://laurentius.lub.lu.se/volumes/Mh_58/ Youngest known Masoretic manuscript | + | * [http://wikisource.org/wiki/Syriac_book_of_genesis Syriac Peshitta book of Genesis (eastern vocalisation)] at Wikisource |

| + | * [http://wikisource.org/wiki/Syriac_book_of_psalms Syriac Peshitta book of Psalms (eastern vocalisation)] at Wikisource | ||

| + | * [http://www.archive.org/details/SyriacPeshitta Syriac Peshitta] New Testament at archive.org | ||

| + | * [http://www.ntcanon.org/Peshitta.shtml The Development of the Canon of the New Testament] | ||

| + | * [http://jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=1035&letter=B Jewish Encyclopedia: Bible Translations] | ||

| + | * [http://laurentius.lub.lu.se/volumes/Mh_58/ Youngest known Masoretic manuscript] Old Testament | ||

* [http://www.aramaicpeshitta.com/ Aramaic Peshitta Bible Repository] | * [http://www.aramaicpeshitta.com/ Aramaic Peshitta Bible Repository] | ||

| - | * [http://www.peshitta.org/ Interlinear Aramaic/English text] | + | * [http://www.peshitta.org/ Interlinear Aramaic/English New Testament] also trilinear Old Testament (Hebrew/Aramaic/English) |

| + | * W. Emery Barnes, [http://www.archive.org/stream/journaltheologi00unkngoog#page/n208/mode/2up ''On the Influence of Septuagint on the Peshitta''], JTS 1901, pp. 186–197. | ||

| + | * Andreas Juckel, [http://syrcom.cua.edu/hugoye/vol8no2/HV8N2Juckel.html ''Septuaginta and Peshitta Jacob of Edessa quoting the Old Testament in Ms BL Add 17134''] JOURNAL OF SYRIAC STUDIES | ||

| + | * [http://tanakh.info Peshitta Tanakh] - Online edition of Syriac Old Testament with a new English translation and Hebrew Masoretic text in parallel. (at present only part of Genesis is available) | ||

| + | * [http://peshitta.info Peshitta] - New English translation of Syriac version of the Old Testament and New Testament. | ||

| + | ;Downloadable cleartext of English translations (Scripture.sf.net): | ||

| + | *[http://sourceforge.net/projects/scripture/files/Bible_Content/English/Lewis_OT_Peshitta%281896%29_eng.bc/download Lewis_OT_Peshitta] (only contains the Pentateuch) | ||

| + | *[http://sourceforge.net/projects/scripture/files/Bible_Content/English/Murdock_NT_Peshitta%281851%29_eng.bc/download Murdock_NT_Peshitta] | ||

| + | *[http://sourceforge.net/projects/scripture/files/Bible_Content/English/Norton_NT_Peshitta%281851%29_eng.bc/download Norton_NT_Peshitta] | ||

| + | *[http://sourceforge.net/projects/scripture/files/Bible_Content/English/Etheridge_NT_Peshitta%281849%29_eng.bc/download Etheridge_NT_Peshitta] | ||

[[Category:Syriac literature]] | [[Category:Syriac literature]] | ||

| - | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Early versions of the Bible]] |

[[Category:Syriac Christianity]] | [[Category:Syriac Christianity]] | ||

[[Category:Christian terms]] | [[Category:Christian terms]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Christian biblical canon]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Bible translations by language|Syriac]] | ||

Revision as of 07:11, 19 November 2012

The Peshitta (Classical Syriac (ܦܹܫܝܼܛܵܐ) for "simple, common, straight, vulgate") sometimes called the Syriac Vulgate) is the standard version of the Bible for churches in the Syriac tradition.

The Old Testament of the Peshitta was translated from the Hebrew, probably in the 2nd century. The New Testament of the Peshitta, which originally excluded certain disputed books (2 Peter, 2 John, 3 John, Epistle of Jude, Revelation), had become the standard by the early 5th century.

The name 'Peshitta'

The name 'Peshitta' is derived from the Syriac mappaqtâ pšîṭtâ (ܡܦܩܬܐ ܦܫܝܛܬܐ), literally meaning 'simple version'. However, it is also possible to translate pšîṭtâ as 'common' (that is, for all people), or 'straight', as well as the usual translation as 'simple'. Syriac is a dialect, or group of dialects, of Eastern Aramaic, originating in and around Assuristan (Persian ruled Assyria). It is written in the Syriac alphabet, and is transliterated into the Latin script in a number of ways: Peshitta, Peshittâ, Pshitta, Pšittâ, Pshitto, Fshitto. All of these are acceptable, but 'Peshitta' is the most conventional spelling in English.

Its Arabic counterpart is البسيطة "Al-Basîṭah", also meaning "The simple [one]".

History of the Syriac versions

Analogy of Latin Vulgate

We have no full and clear knowledge of the circumstances under which the Peshitta was produced and came into circulation. Whereas the authorship of the Latin Vulgate has never been in dispute, almost every assertion regarding the authorship of the Peshitta, and the time and place of its origin, is subject to question. The chief ground of analogy between the Vulgate and the Peshitta is that both came into existence as the result of a revision. This, indeed, has been strenuously denied, but since Dr. Hort in his Introduction to Westcott and Hort's New Testament in the Original Greek, following Griesbach and Hug at the beginning of the 19th century, maintained this view, it has gained many adherents. So far as the Gospels and other New Testament books are concerned, there is evidence in favor of this view which has been added to by recent discoveries; and fresh investigation in the field of Syriac scholarship has raised it to a high degree of probability. The very designation, "Peshito," has given rise to dispute. It has been applied to the Syriac as the version in common use, and regarded as equivalent to the Greek koine and the Latin Vulgate.[]

The Designation "Peshito" ("Peshitta")

The word itself is a feminine form, meaning "simple," "easy to be understood." It seems to have been used to distinguish the version from others which are encumbered with marks and signs in the nature of a critical apparatus. However this may be, the term as a designation of the version has not been found in any Syriac author earlier than the 9th or 10th century.

As regards the Old Testament, the antiquity of the Version is admitted on all hands. The tradition, however, that part of it was translated from Hebrew into Syriac for the benefit of Hiram in the days of Solomon is a myth. That a translation was made by a priest named Assa, or Ezra, whom the king of Assyria sent to Samaria, to instruct the Assyrian colonists mentioned in 2 Kings 17, is equally legendary. That the translation of the Old Testament and New Testament was made in connection with the visit of Thaddaeus to Abgar at Edessa belongs also to unreliable tradition. Mark has even been credited in ancient Syriac tradition with translating his own Gospel (written in Latin, according to this account) and the other books of the New Testament into Syriac.[1]

Syriac Old Testament

But what Theodore of Mopsuestia says of the Old Testament is true of both: "These Scriptures were translated into the tongue of the Syriacs by someone indeed at some time, but who on earth this was has not been made known down to our day".[2] F. Crawford Burkitt concluded that the translation of the Old Testament was probably the work of Jews, of whom there was a colony in Edessa about the commencement of the Christian era.[3] The older view was that the translators were Christians, and that the work was done late in the 1st century or early in the 2nd. The Old Testament known to the early Syrian church was substantially that of the Palestinian Jews. It contained the same number of books but it arranged them in a different order. First there was the Pentateuch, then Job, Joshua, Judges, 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Kings, 1 and 2 Chronicles, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Ruth, Canticles, Esther, Ezra, Nehemiah, Isaiah followed by the Twelve Minor Prophets, Jeremiah and Lamentations, Ezekiel, and lastly Daniel. Most of the apocryphal books of the Old Testament are found in the Syriac, and the Wisdom of Sirach is held to have been translated from the Hebrew and not from the Septuagint.[1]

Syriac New Testament

Of the New Testament, attempts at translation must have been made very early, and among the ancient versions of New Testament Scripture the Syriac in all likelihood is the earliest. It was at Antioch, the capital of Syria, that the disciples of Christ were first called Christians, and it seemed natural that the first translation of the Christian Scriptures should have been made there. Some research, however, goes to show that Edessa, the literary capital, could have been the place.

If we could accept the somewhat obscure statement of Eusebius[4] that Hegesippus "made some quotations from the Gospel according to the Hebrews and from the Syriac Gospel," we should have a reference to a Syriac New Testament as early as 160-80 AD, the time of that Hebrew Christian writer. One thing is certain, that the earliest New Testament of the Syriac church lacked not only the Antilegomena – 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, Jude, and the Apocalypse – but the whole of the Catholic Epistles. These were at a later date translated and received into the Syriac Canon of the New Testament, but the quotations of the early Syrian Fathers take no notice of these New Testament books.

From the 5th century, however, the Peshitta containing both Old Testament and New Testament has been used in its present form only as the national version of the Syriac Scriptures. The translation of the New Testament is careful, faithful and literal, and the simplicity, directness and transparency of the style are admired by all Syriac scholars and have earned for it the title of "Queen of the versions." [1]

Old Syriac texts

It is in the Gospels, however, that the analogy between the Latin Vulgate and the Syriac Vulgate can be established by evidence. If the Peshitta is the result of a revision as the Vulgate was, then we may expect to find Old Syriac texts answering to the Old Latin. Such texts have actually been found. Three such texts have been recovered, all showing divergences from the Peshitta, and believed by competent scholars to be anterior to it. These are, to take them in the order of their recovery in modern times, (1) the Curetonian Syriac, (2) the Syriac of Tatian's Diatessaron, and (3) the Sinaitic Syriac.[1]</sup>

- Details on Curetonian

- Details on Tatian's Diatessaron

- Sinaitic Syriac

- Relation to Peshitta

Brief History of the Peshitta

The Peshitta had from the 5th century onward a wide circulation in the East, and was accepted and honored by all the numerous sects of the greatly divided Syriac Christianity. It had a great missionary influence, and the Armenian and Georgian versions, as well as the Arabic and the Persian, owe not a little to the Syriac. The famous Nestorian tablet of Sing-an-fu witnesses to the presence of the Syriac Scriptures in the heart of China in the 7th century. It was first brought to the West by Moses of Mindin, a noted Syrian ecclesiastic, who sought a patron for the work of printing it in vain in Rome and Venice, but found one in the Imperial Chancellor at Vienna in 1555—Albert Widmanstadt. He undertook the printing of the New Testament, and the emperor bore the cost of the special types which had to be cast for its issue in Syriac. Immanuel Tremellius, the converted Jew whose scholarship was so valuable to the English reformers and divines, made use of it, and in 1569 issued a Syriac New Testament in Hebrew letters. In 1645 the editio princeps of the Old Testament was prepared by Gabriel Sionita for the Paris Polyglot, and in 1657 the whole Peshitta found a place in Walton's London Polyglot. For long the best edition of the Peshitta was that of John Leusden and Karl Schaaf, and it is still quoted under the symbol Syrschaaf, or SyrSch. The critical edition of the Gospels recently issued by Mr. G. H. Gwilliam at the Clarendon Press is based upon some 50 manuscripts. Considering the revival of Syriac scholarship, and the large company of workers engaged in this field, we may expect further contributions of a similar character to a new and complete critical edition of the Peshitta.[1]

Old Testament Peshitta

The Peshitta version of the Old Testament is an independent translation based largely on a Hebrew text similar to the Proto-Masoretic Text. It shows a number of linguistic and exegetical similarities to the Aramaic Targums but is now no longer thought to derive from them. In some passages the translators have may have used the Greek Septuagint. The influence of the Septuagint is particularly strong in Isaiah and the Psalms, probably due to their use in the liturgy. Most of the Deuterocanonicals are translated from the Septuagint, and the translation of Sirach was based on a Hebrew text.

The choice of books included in the Old Testament Peshitta changes from one manuscript to another. Usually most of the Deuterocanonicals are present. Other Biblical apocryphas, as 1 Esdras, 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, Psalm 151 can be found in some manuscripts. The manuscript of Biblioteca Ambrosiana, discovered in 1866, includes also 2 Baruch (Syriac Apocalypse of Baruch).

Main manuscripts

More than 250 manuscripts of the Old Testament Peshitta are known, and the main and older ones are:

- London, British Library, Add. 14,425 (also referred to as "5b1" in Leiden numeration): dated in the second half of 5th century, it includes only Genesis, Exodus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The text is more similar to the Masoretic Text than the text of most other manuscripts, even if somewhere it has relevant differences.

- Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, B. 21 inf (also referred to as "7a1"): it was discovered by Antonio Ceriani in 1866 and published in 1876-1883. This manuscript dates from the sixth or the 7th century. In 1006/7 it became part of the library of the Syrian Monastery in Egypt and in the 17th century was moved to Milan. The text is used as base text in the critical edition of Peshitta Institute of Leiden. It includes all the books of the Hebrew Bible and Wisdom (of Solomon), Letter of Jeremiah, Baruch, Bel and the Dragon, Susanna, Judith, Sirach, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 2 Baruch (the only extant manuscript in Syriac) with the Letter of Baruch, 2 Esdras, and the second book of The Jewish War[7]

- Paris, Bibliothèque National, Syr. 341 (also referred to as "8a1"): it dates from the eight century or even before and has many corrections. It includes all the books of the Hebrew Bible and Wisdom (of Solomon), Letter of Jeremiah, Baruch, Bel and the Dragon, Susanna, Judith, Sirach, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, 3 Maccabees, Odes, Prayer of Manasseh, Letter of Baruch[7]

- Florence, Laurentian Library, Or. 58 (also referred to as "9a1"): this manuscript has a text more similar to the Masoretic Text as "5b1" has, and scholars don't know if this is due to a more original text, or to later corrections. It includes all the books of the Hebrew Bible and Bel and the Dragon, Susanna, Judith, Prayer of Manasseh[7]

- Cambridge, University Library, Oo.I.1,2 (also referred to as "12a1" or as "Buchanan Bible"): it is a 12th century manuscript that probably originated in Tur Abdin area, and was later moved to India and later to Cambridge by Claudius Buchanan in the early 19th century. It is the best testimony of an important textual family. It includes all the books of the Hebrew Bible and Wisdom (of Solomon), Letter of Jeremiah, Baruch, Bel and the Dragon, Susanna, Judith, Sirach, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, Tobit, 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, Letter of Baruch[7]

- Baghdad, Library of Chaldean Patriarchate, 211 (Mosul cod. 4): 12th century manuscript used often as base text for Psalms 152–155

Early print editions

- Paris Polyglot, 1645, edited by Gabriel Sionita and probably based on manuscript "17a5", considered today a recent and not reliable manuscript.

- London Polyglot, 1657, based on the Paris Polyglot text with an appendix of the some collations from other manuscripts kept in Oxford ranging form the 12th to the 17th century.

- Samuel Lee edition, first printed in London in 1823 by the British and Foreign Bible Society and reprinted in 1826. The text is almost like the London Polyglot's one. In the 1826 the British and Foreign Bible Society decided to cut from each printed copy of this Bible the page containing the Psalm 151 because this Psalm is not in the Protestant canon.[8]

- Urmia Bible, published in 1852 by Justin Perkins, that included also a parallel translation in the Urmian dialect of Assyrian Neo-Aramaic language.

- Mosul edition, published in 1888-1892 by Clement Joseph David [9] and by Mar Georges Ebed-Iesu Khayyath for the Dominican mission. This edition, differently from previously editions, includes also some books not in the Hebrew Bible but found in many Peshitta manuscripts: these books included are: Tobit, Judith, Additions to Esther, Wisdom (of Solomon), Sirach, Letter of Jeremiah, Baruch, Bel and the Dragon, Susanna, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, 2 Baruch with the Letter of Baruch.

New Testament Peshitta

The Peshitta version of the New Testament is thought to show a continuation of the tradition of the Diatessaron and Old Syriac versions, displaying some lively 'Western' renderings (particularly clear in the Acts of the Apostles). It combines with this some of the more complex 'Byzantine' readings of the 5th century. One unusual feature of the Peshitta is the absence of 2 Peter, 2 John, 3 John, Jude and Revelation. Modern Syriac Bibles add 6th or 7th century translations of these five books to a revised Peshitta text.

Almost all Syriac scholars agree that the Peshitta gospels are translations of the Greek originals. A minority viewpoint (see Aramaic primacy) is that the Peshitta represent the original New Testament and the Greek is a translation of it. The type of text represented by Peshitta is the Byzantine. In a detailed examination of Matthew 1-14, Gwilliam found that the Peshitta agrees with the Textus Receptus only 108 times and with Codex Vaticanus 65 times, while in 137 instances it differs from both, usually with the support of the Old Syriac and the Old Latin, in 31 instances is stands alone.[10]

In reference to the originality of the Peshitta, the words of Patriarch Mar Eshai Shimun XXIII are summarized as follows:

- "With reference to....the originality of the Peshitta text, as the Patriarch and Head of the Holy Apostolic and Catholic Church of the East, we wish to state, that the Church of the East received the scriptures from the hands of the blessed Apostles themselves in the Aramaic original, the language spoken by our Lord Jesus Christ Himself, and that the Peshitta is the text of the Church of the East which has come down from the Biblical times without any change or revision."[11]

For more information, see Aramaic New Testament.

Critical edition of the New Testament

The standard United Bible Societies 1905 edition of the New Testament of the Peshitta was based on editions prepared by Syriacists Philip E. Pusey (d.1880), George Gwilliam (d.1914) and John Gwyn.[12] These editions comprised Gwilliam & Pusey's 1901 critical edition of the Gospels, Gwilliam's critical edition of Acts, Gwilliam & Pinkerton's critical edition of Paul's Epistles and John Gwynn's critical edition of the General Epistles and later Revelation. This critical Peshitta text is based on a collation of more than seventy Peshitta and a few other Aramaic manuscripts. All twenty seven books of the common western canon of the New Testament are included in this British & Foreign Bible Society's 1905 Peshitta edition, as is the adultery pericope (John 7:53-8:11). The 1979 Syriac Bible, United Bible Society, uses the same text for its New Testament. The Online Bible reproduces the 1905 Syriac Peshitta NT in Hebrew characters.

Translations of the Peshitta

Both John Wesley Etheridge (1846–1849) and James Murdock (1852)[13] produced translations of the New Testament Peshitta in the 19th century. More recently various versions of the New Testament only have appeared arguing this view in the notes. These include:

- George M. Lamsa- The Holy Bible From the Ancient Eastern Text (1933)- The only complete English work of both the Old and New Testaments according to the Peshitta text. Lamsa was a native Syriac speaker. This work is better known as the Lamsa Bible. He also wrote several other books on the Peshitta and Aramaic Primacy such as Gospel Light, New Testament Origin, and Idioms of the Bible, along with a New Testament commentary. Several well-known evangelists used or endorsed the Lamsa Bible, such as Oral Roberts, Billy Graham, and William M. Branham. Is not accepted as a translation by formal academics and translators, because Lamsa mixed their very personal nationalist and esoteric Assyrian concepts enclosed on bible text, therefore, is not a serious bible translation but a personal mixed narrative of bible verses, esoteric concepts and wrong doctrine with extra-biblical elements.

- Andrew Gabriel Roth- Aramaic English New Testament (AENT), which includes a literal translation of the Peshitta on the left side pages with the Aramaic text in Hebrew letters on the right side with Roth's commentary. The AENT is basically a revision of the Younan Interlinear New Testament (from Matthew 1 to Acts 15) and the James Murdock's (Acts 15 and onward). [14]

- Janet Magiera- Aramaic Peshitta New Testament Translation, Aramaic Peshitta New Testament Translation- Messianic Version, and Aramaic Peshitta Vertical Interlinear (in three volumes). Magiera was an associate of George Lamsa.

- Reverend Glenn David Bauscher- The Aramaic-English Interlinear New Testament (1st edition 2006), Psalms, Proverbs & Ecclesiastes (4th edition 2011) [15] the basis for The Original Aramaic New Testament in Plain English (2007, 6th edition 2011). Another literal translation that comes as an interlinear New Testament (with Hebrew characters), and a smoother English version. Bauscher translated from the Western Peshitto text.[16]

- Victor Alexander- Aramaic New Testament and Disciples New Testament. Alexander is a native speaker of Syriac.

- The Way International- The Aramaic Interlinear Bible

- Paul Younan, a native Syriac speaker, is currently working on an interlinear translation of the Peshitta into English.

- Arch-corepiscopos Curien Kaniamparambil- Vishudhagrandham Peshitta translation (including Old and New Testaments) in Malayalam, the language of Kerala.

In Spanish exists Biblia Peshitta en Español (Spanish Peshitta Bible) by Holman Bible Publishers, Nashville, TN. U. S. A., published 2007.

Manuscripts of the New Testament

The following manuscripts are in the British Archives.

- British Library, Add. 14470 – complete text of 22 books, from the 5th/6th century

- Rabbula Gospels

- Khaboris Codex

- Codex Phillipps 1388

- British Library, Add. 12140

- British Library, Add. 14479

- British Library, Add. 14455

- British Library, Add. 14466

- British Library, Add. 14467

- British Library, Add. 14669

About 1963, Mr. Lamsa finally found a publisher for his (Translation), World Bible Publishers, New York. The (relationship) was short-lived, however..and again, Mr. Lamsa went looking for a Publisher. In 1966, Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association agreed to use their printing presses to resume (the task). At that time, Vernon Hale was Editor and his wife still possesses the First (signed-dedicated copy), along with a few other gifts from Mr. Lamsa. Formal academics and translators of Peshitta text have revealed that Lamsa's work is not a serious translation, but a personal narrative mixed with esoteric and nationalist Assyrian concepts.

Notes

- 1. Syriac Versions of the Bible by Thomas Nicol

- 2. Eberhard Nestle in Hastings' Dictionary of the Bible, IV, 645b.

- 3. Francis Crawford Burkitt, Early Eastern Christianity, 71 ff. 1904.

- 4. Historia Ecclesiastica, IV, xxii

- 5. Tetraevangelium sanctum, Clarendon Press, 1901

- 6. Evangelion da-Mepharreshe, 186.

- 7. For the order of the books see S. Brock, The Bible in the Syriac Tradition ISBN 1-59333-300-5 p. 116

- 8. A. S. van der Woude In Quest of the Past ISBN 90-04-09192-0 (1988), p. 70

- 9. Syriac Catholic Archbishop of Damascus, born 1829

- 10. Bruce M. Metzger, The Early Versions of the New Testament: Their Origin, Transmission and Limitations (Oxford University Press 1977), p. 50.

- 11. His Holiness Mar Eshai Shimun, Catholicos Patriarch of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Church of the East. April 5, 1957

- 12. Corpus scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium: Subsidia Catholic University of America, 1987 "37 ff. The project was founded by Philip E. Pusey who started the collation work in 1872. However, he could not see it to completion since he died in 1880. Gwilliam,

- 13. The New Testament of the Book of the Holy Gospel of our Lord and our God Jesus the Messiah a Literal Translation from the Syriac Peshito Version.

- 14. Andrew Gabriel Roth, Aramaic English New Testament, Netzari Press, Third Edition (2010), ISBN 1-934916-26-9 - included all twenty-seven books of the Aramaic New Testament, as a literal translation of the very oldest known Aramaic New Testament texts. This is a study Bible with over 1700 footnotes and 350 pages of appendixes to help the reader understand the poetry, idioms, terms and definitions in the language of Y'shua (Jesus) and his followers. The Aramaic is featured with Hebrew letters and vowel pointing.

- 15. The Aramaic-English Interlinear New Testament 4th edition 2011

- 16. The Original Aramaic New Testament in Plain English, 6th edition 2011 has also Psalms & Proverbs in plain English from his Peshitta interlinear of those Peshitta Old Testament books, according to Codex Ambrosianus (6th century?) and Lee's 1816 edition of the Peshitta Old Testament. Bauscher has also published an Aramaic-English & English Aramaic Dictionary & nine other books related to the Peshitta Bible. The interlinear displays the Aramaic in Ashuri (square Hebrew) letters.

Sources

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2006) The Bible in the Syriac Tradition: English Version Gorgias Press LLC, ISBN 1-59333-300-5

- Dirksen, P. B. (1993). La Peshitta dell'Antico Testamento, Brescia, ISBN 88-394-0494-5

- Flesher, P. V. M. (ed.) (1998). Targum Studies Volume Two: Targum and Peshitta. Atlanta.

- Kiraz, George Anton (1996). Comparative Edition of the Syriac Gospels: Aligning the Old Syriac Sinaiticus, Curetonianus, Peshitta and Harklean Versions. Brill: Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2002 [2nd ed.], 2004 [3rd ed.].

- Lamsa, George M. (1933). The Holy Bible from Ancient Eastern Manuscripts. ISBN 0-06-064923-2.

- Pinkerton, J. and R. Kilgour (1920). The New Testament in Syriac. London: British and Foreign Bible Society, Oxford University Press.

- Pusey, Philip E. and G. H. Gwilliam (1901). Tetraevangelium Sanctum iuxta simplicem Syrorum versionem. Oxford University Press.

- Weitzman, M. P. (1999). The Syriac Version of the Old Testament: An Introduction. ISBN 0-521-63288-9.

- Attribution

- Nicol, Thomas. "Syriac Versions" in (1915) International Standard Bible Encyclopedia

See also

External links

- Dukhrana Biblical Research

- Syriac Peshitta book of Genesis (eastern vocalisation) at Wikisource

- Syriac Peshitta book of Psalms (eastern vocalisation) at Wikisource

- Syriac Peshitta New Testament at archive.org

- The Development of the Canon of the New Testament

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Bible Translations

- Youngest known Masoretic manuscript Old Testament

- Aramaic Peshitta Bible Repository

- Interlinear Aramaic/English New Testament also trilinear Old Testament (Hebrew/Aramaic/English)

- W. Emery Barnes, On the Influence of Septuagint on the Peshitta, JTS 1901, pp. 186–197.

- Andreas Juckel, Septuaginta and Peshitta Jacob of Edessa quoting the Old Testament in Ms BL Add 17134 JOURNAL OF SYRIAC STUDIES

- Peshitta Tanakh - Online edition of Syriac Old Testament with a new English translation and Hebrew Masoretic text in parallel. (at present only part of Genesis is available)

- Peshitta - New English translation of Syriac version of the Old Testament and New Testament.

- Downloadable cleartext of English translations (Scripture.sf.net)

- Lewis_OT_Peshitta (only contains the Pentateuch)

- Murdock_NT_Peshitta

- Norton_NT_Peshitta

- Etheridge_NT_Peshitta