Dead Sea scrolls

From Textus Receptus

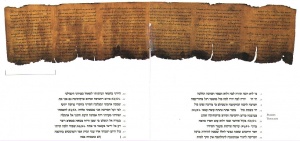

The Dead Sea scrolls consist of about 900 documents, including texts from the Hebrew Bible, discovered between 1947 and 1956 in eleven caves in and around the Qumran Wadi near the ruins of the ancient settlement of Khirbet Qumran, on the northwest shore of the Dead Sea.

The texts are of great religious and historical significance, as they include some of the only known surviving copies of Biblical documents made before 100 BCE and preserve evidence of late Second Temple Judaism. They are written in Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek, mostly on parchment, but with some written on papyrus.<ref>From papyrus to cyberspace The Guardian August 27, 2008.</ref> These manuscripts generally date between 150 BCE to 70 CE.<ref>Bruce, F. F.. "The Last Thirty Years". Story of the Bible. ed. Frederic G. Kenyon Retrieved June 19, 2007</ref> The scrolls are most commonly identified with the ancient Jewish sect called the Essenes, though some recent interpretations have challenged their association with the scrolls.<ref>Ilani, Ofri, "Scholar: The Essenes, Dead Sea Scroll 'authors,' never existed, Ha'aretz, March 13, 2009</ref> Still, these represent a minority view, as references in ancient texts from Josephus, Philo, and Pliny all discuss the Essenes, with Pliny identifying the center of Essene activity on the west side of the Dead Sea, exactly where the scrolls were found.<ref> Larson, Martin A, The Story of Christian Origins, Washington, D.C., New Republic Books, 1977 ppg 227-228</ref> Moreover, Philo and Josephus both extensively describe the customs and beliefs of the Essenes, in many cases closely matching information found in the scrolls themselves.<ref>Larson, Martin A, The Story of Christian Origins, Washington, D.C., New Republic Books, 1977 ppg 236-246</ref> This is not surprising, since Josephus reports in his Life that at the age of sixteen he became an Essene neophyte for three years.<ref>Larson, Martin A, The Story of Christian Origins, Washington, D.C., New Republic Books, 1977 pg 240</ref>

The Dead Sea Scrolls are traditionally divided into three groups: "Biblical" manuscripts (copies of texts from the Hebrew Bible), which comprise roughly 40% of the identified scrolls; "Apocryphal" or "Pseudepigraphical" manuscripts (known documents from the Second Temple Period like Enoch, Jubilees, Tobit, Sirach, non-canonical psalms, etc., that were not ultimately canonized in the Hebrew Bible), which comprise roughly 30% of the identified scrolls; and "Sectarian" manuscripts (previously unknown documents that speak to the rules and beliefs of a particular group or groups within greater Judaism) like the Community Rule, War Scroll, Pesher (Hebrew pesher פשר = "Commentary") on Habakkuk, and the Rule of the Blessing, which comprise roughly 30% of the identified scrolls.<ref>Abegg, Jr., Martin, Peter Flint, and Eugene Ulrich, The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible: The Oldest Known Bible Translated for the First Time into English, San Francisco: Harper, 2002</ref>

Prior to 1968, most of the known scrolls and fragments were housed in the Rockefeller Museum (formerly known as the Palestine Archaeological Museum) in Jerusalem. After the Six Day War, these scrolls and fragments were moved to the Shrine of the Book, at the Israel Museum.

Publication of the scrolls has taken many decades, and the delay has been a source of academic controversy. As of 2007 two volumes remain to be completed, with the whole series, Discoveries in the Judean Desert, running to thirty-nine volumes in total. Many of the scrolls are now housed in the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem, while others are housed in the University of Chicago's Oriental Institute, Princeton Theological Seminary, Azusa Pacific University, and in the hands of private collectors. According to The Oxford Companion to Archeology, "The biblical manuscripts from Qumran, which include at least fragments from every book of the Old Testament, except perhaps for the Book of Esther, provide a far older cross section of scriptural tradition than that available to scholars before. About 35% of the Qumran biblical manuscripts are nearly identical to the Masoretic, or traditional, Hebrew text of the Old Testament and 10% to the Greek and Samaritan traditions, with the remainder exhibiting sometimes dramatic differences in both language and content. In their range of textual variants, the Qumran biblical discoveries have prompted scholars to reconsider the once-accepted theories of the development of the modern biblical text from only three manuscript families: of the Masoretic text, of the Hebrew original of the Septuagint, and of the Samaritan Pentateuch. It is now becoming increasingly clear that the Old Testament scripture was extremely fluid until its canonization around 100 AD."<ref>Fagan, Brian M., and Charlotte Beck, The Oxford Companion to Archeology, entry on the "Dead sea scrolls", Oxford University Press, 1996</ref> thumb|300px|Fragments of the scrolls on display at the Archaeological Museum, Amman

Contents |

Discovery

thumb|The caves in which the scrolls were found thumb|Remains of the west wing of the main building at Qumran. The settlement of Qumran is 1 km inland from the northwest shore of the Dead Sea. The scrolls were found in eleven caves nearby, between 125m (Cave 4) and 1 km (Cave 1) away. None were found within the settlement, unless it originally encompassed the caves. In the winter of 1946–47, Muhammed edh-Dhib and his cousin discovered the caves, and soon afterwards the scrolls.

John C. Trever reconstructed the story of the scrolls from several interviews with the Bedouin. edh-Dhib's cousin noticed the caves, but edh-Dhib himself was the first to actually fall into one. He retrieved a handful of scrolls, which Trever identifies as the Isaiah Scroll, Habakkuk Commentary, and the Community Rule (originally known as "Manual of Discipline"), and took them back to the camp to show to his family. None of the scrolls was destroyed in this process, despite popular rumor.<ref name="ReferenceA">John C. Trever. The Dead Sea Scrolls. Gorgias Press LLC, 2003</ref> The Bedouin kept the scrolls hanging on a tent pole while they figured out what to do with them, periodically taking them out to show people. At some point during this time, the Community Rule was split in two.

The Bedouin first took the scrolls to a dealer named Ibrahim 'Ijha in Bethlehem. 'Ijha returned them, saying they were worthless, after being warned that they may have been stolen from a synagogue. Undaunted, the Bedouin went to a nearby market, where a Syrian Christian offered to buy them. A sheikh joined their conversation and suggested they take the scrolls to Khalil Eskander Shahin, "Kando", a cobbler and part-time antiques dealer. The Bedouin and the dealers returned to the site, leaving one scroll with Kando and selling three others to a dealer for £7 GBP ($29 in 2003 US dollars).<ref name="ReferenceA" />

Arrangements with the Bedouin left the scrolls in the hands of a third party until a profitable sale of them could be negotiated. That third party, George Isha'ya, was a member of the Syrian Orthodox Church, who soon contacted St. Mark's Monastery in the hope of getting an appraisal of the nature of the texts. News of the find then reached Metropolitan Athanasius Yeshue Samuel, better known as Mar Samuel.

After examining the scrolls and suspecting their antiquity, Mar Samuel expressed an interest in purchasing them. Four scrolls found their way into his hands: the now famous Isaiah Scroll (1QIsa), the Community Rule, the Habakkuk Pesher (a commentary on the book of Habakkuk), and the Genesis Apocryphon. More scrolls soon surfaced in the antiquities market, and Professor Eleazer Sukenik and Prof. Benjamin Mazar, Israeli archaeologists at Hebrew University, soon found themselves in possession of three, The War Scroll, Thanksgiving Hymns, and another, more fragmented, Isaiah scroll.

By the end of 1947, Sukenik and Mazar received word of the scrolls in Mar Samuel's possession and attempted to purchase them. No deal was reached, and instead the scrolls caught the attention of Dr. John C. Trever, of the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR), who compared the script in the scrolls to that of The Nash Papyrus, the oldest biblical manuscript then known, and found similarities between them.

Dr. Trever, a keen amateur photographer, met with Mar Samuel on February 21, 1948, when he photographed the scrolls. The quality of his photographs often exceeded the visibility of the scrolls themselves over the years, as the ink of the texts quickly deteriorated after they were removed from their linen wrappings.

thumb|right|Ad for "Dead Sea Scrolls" in the Wall Street Journal

The scrolls were analyzed using a cyclotron at the University of California, Davis where it was found that the black ink used was iron-gall ink.<ref name="realscience"> {{#invoke:citation/CS1|citation |CitationClass=web }} </ref> The red ink on the scrolls was cinnabar (HgS, mercury sulfide).<ref name="realscience" />

In March, the 1948 Arab-Israeli War prompted the removal of the scrolls for safekeeping, from Israel to Beirut, Lebanon.

Early in September, 1948, Mar Samuel brought Professor Ovid R. Sellers, the new Director of ASOR, some additional scroll fragments that he had acquired. By the end of 1948, nearly two years after their discovery, scholars had yet to locate the cave where the fragments had been found. With unrest in the country at that time, no large-scale search could be undertaken. Sellers attempted to get the Syrians to help him locate the cave, but they demanded more money than he could offer. Finally, Cave 1 was discovered, on January 28, 1949, by a United Nations observer.

The Dead Sea Scrolls went up for sale eventually, in an advertisement in the June 1, 1954 Wall Street Journal.

On July 1, the scrolls, after delicate negotiations and accompanied by three people including the Metropolitan, arrived at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York. They were purchased by Prof. Mazar and the son of Prof. Sukenik, Yigael Yadin, for US$250,000 and brought back to Jerusalem, where they are on display at the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum.

Survey of the Caves

Cave 1

Cave 1 was discovered in the winter or spring of 1947. It was first excavated by Gerald Lankester Harding and Roland de Vaux from Feb 15 to Mar 5, 1949.<ref>VanderKam, James C., The Dead Sea Scrolls Today, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994. p. 9.</ref> In addition to the original seven scrolls, Cave 1 produced jars and bowls, whose chemical composition and shape matched vessels discovered at the settlement at Qumran, pieces of cloth, and additional fragments that matched portions of the original scrolls, thereby confirming that the original scrolls came from Cave 1.

The original seven scrolls from Cave 1 are:<ref name="Vermes 1998">Vermes, Geza, The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English, London: Penguin, 1998. ISBN 0-14-024501-4</ref>

- 1QIsaa (a copy of the book of "Isaiah")

- 1QIsab (a second copy of the book of "Isaiah")

- 1QS ("Community Rule") cf. 4QSa-j = 4Q255-64, 5Q11

- 1QpHab ("Pesher on Habakkuk")

- 1QM ("War Scroll") cf. 4Q491, 4Q493

- 1QH ("Thanksgiving Hymns")

- 1QapGen ("Genesis Apocryphon")

Cave 2

Cave two was discovered in February, 1952.<ref name="VanderKam, James C. 1994. p. 10">VanderKam, James C., The Dead Sea Scrolls Today, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994. p. 10.</ref> It yielded 300 fragments from 33 manuscripts, including Jubilees and the Wisdom of Ben-Sirach in the original Hebrew.

Cave 3

Cave three was discovered on March 14, 1952.<ref name="VanderKam, James C. 1994. p. 10" /> The cave yielded 14 manuscripts including Jubilees and the curious Copper Scroll, which lists 67 hiding places, mostly underground, throughout the ancient Roman province of Judea (now Israel and Palestine). According to the scroll, the secret caches held astonishing amounts of gold, silver, copper, aromatics, and manuscripts.

Cave 4

Cave four was discovered in August, 1952, and was excavated from September 22 to 29, 1952 by Gerald Lankester Harding, Roland de Vaux, and Józef Milik.<ref name="VanderKam, James C. 1994. p. 10-11">VanderKam, James C., The Dead Sea Scrolls Today, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994. p. 10-11.</ref> Cave four is actually two caves (4a and 4b), but since the fragments were mixed, they are labeled as 4Q. Cave 4 is the most famous of Qumran caves both because of its visibility and its productivity. It is visible from the plateau to the south of the Qumran settlement. It is by far the most productive of all Qumran caves, producing ninety percent of the Dead Sea Scrolls and scroll fragments (approx. 15,000 fragments from 500 different texts), including 9-10 copies of Jubilees, along with 21 tefillin and 7 mezuzot.

Caves 5 and 6

Caves 5 and 6 were discovered in 1952, shortly after Cave 4. Cave 5 produced approximately 25 manuscripts, while Cave 6 contained fragments of about 31 manuscripts.<ref name="VanderKam, James C. 1994. p. 10-11" />

Caves 7–9

Caves 7-9 are unique in that they are the only caves that are accessible only by passing through the settlement at Qumran. Carved into the southern end of the Qumran plateau, archaeologists excavated caves 7-9 in 1957, but did not find many fragments perhaps due to high levels of erosion that left only the shallow bottoms of the caves.

Cave 7 yielded fewer than 20 fragments of Greek documents, including 7Q2 (the "Letter of Jeremiah" = Baruch 6), 7Q5 (which became the subject of much speculation in later decades), and a Greek copy of a scroll of Enoch.<ref>Baillet, Maurice ed. Les ‘Petites Grottes’ de Qumrân (ed., vol. 3 of Discoveries in the Judean Desert; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1962), 144–45, pl. XXX.</ref><ref>Muro, Ernest A., “The Greek Fragments of Enoch from Qumran Cave 7 (7Q4, 7Q8, &7Q12 = 7QEn gr = Enoch 103:3–4, 7–8),” Revue de Qumran 18 no. 70 (1997).</ref><ref>Puech, Émile, “Sept fragments grecs de la Lettre d’Hénoch (1 Hén 100, 103, 105) dans la grotte 7 de Qumrân (= 7QHén gr),” Revue de Qumran 18 no. 70 (1997).</ref> Cave 7 also produced several inscribed potsherds and jars.<ref name="ReferenceB">Humbert and Chambon, Excavations of Khirbet Qumran and Ain Feshkha, 67.</ref>

Cave 8 produced five fragments: Genesis (8QGen), Psalms (8QPs), a tefillin fragment (8QPhyl), a mezuzah (8QMez), and a hymn (8QHymn).<ref>Baillet ed. Les ‘Petites Grottes’ de Qumrân (ed.), 147–62, pl. XXXIXXXV.</ref> Cave 8 also produced several tefillin cases, a box of leather objects, lamps, jars, and the sole of a leather shoe.<ref name="ReferenceB" />

Cave 9 produced only small, unidentifiable fragments.

Caves 8 and 9 also yielded several date pits<ref name="ReferenceB" /> similar to those discovered by Magen and Peleg to the west of Locus 75 during their "Operation Scroll" excavations.<ref>Wexler, Lior ed. Surveys and Excavations of Caves in the Northern Judean Desert (CNJD) - 1993 (‘Atiqot 41; 2 vols.; Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 2002).</ref><ref>Magen, Yizhak and Yuval Peleg, The Qumran Excavations 1993–2004: Preliminary Report (Judea & Samaria Publications 6; Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 2007), 7.</ref>

Cave 10

Cave 10 produced only a single ostracon with some writing on it.

Cave 11

Cave 11 was discovered in 1956 and yielded 21 texts, some of which were quite lengthy. The Temple Scroll, so called because more than half of it pertains to the construction of the Temple of Jerusalem, was found in Cave 11, and is by far the longest scroll. It is now 26.7 feet (8.15m) long. Its original length may have been over 28 feet (8.75m). The Temple Scroll was regarded by Yigael Yadin as "The Torah According to the Essenes." On the other hand, Hartmut Stegemann, a contemporary and friend of Yadin, believed the scroll was not to be regarded as such, but was a document without exceptional significance. Stegemann notes that it is not mentioned or cited in any known Essene writing.<ref>Stegemann, Hartmut. "The Qumran Essenes: Local Members of the Main Jewish Union in Late Second Temple Times." Pages 83-166 in The Madrid Qumran Congress: Proceedings of the International Congress on the Dead Sea Scrolls, Madrid, 18-21 March 1991, Edited by J. Trebolle Barrera and L. Vegas Montaner. Vol. 11 of Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah. Leiden: Brill, 1992.</ref>

Also in Cave 11, an escatological fragment about the biblical figure Melchizedek (11Q13) was found. Cave 11 also produced a copy of Jubilees.

Survey of Scrolls

While many of the Dead Sea Scrolls are small fragments of Biblical, apocryphal, or sectarian manuscripts, some of the scrolls have come to be well known and influential to Second Temple Judaism. The following is a brief list of some of the more widely known Dead Sea Scrolls:<ref name="Vermes 1998" />

- 1QIsaa (a copy of the book of "Isaiah")

- 1QIsab (a second copy of the book of "Isaiah")

- 1QS ("Community Rule") cf. 4QSa-j = 4Q255-64, 5Q11

- 1QpHab ("Pesher on Habakkuk")

- 1QM ("War Scroll") cf. 4Q491, 4Q493; 11Q14?

- 1QH ("Thanksgiving Hymns")

- 1QapGen ("Genesis Apocryphon")

- CD ("Damascus Document") cf. 4QDa/g = 4Q266/272, 4QDa/e = 4Q266/270, 5Q12, 6Q15, 4Q265-73

- 1QSa ("Rule of the Congregation")

- 1QSb ("Rule of the Blessing") = 1Q28b

- 1Q14 ("Pesher on Micah")

- 2Q18 ("Sirach" or "Wisdom of Jesus ben Sira" or "Ecclesiasticus")

- 3Q7 ("Testament of Judah") = 4Q484, 4Q538

- 3Q15 ("Copper Scroll")

- 4QCantb ("Pesher on Canticles or "Pesher on the Song of Songs) = 4Q107

- 4QCantc ("Pesher on Canticles or "Pesher on the Song of Songs) = 4Q108

- 4Q112 ("Daniel")

- 4Q123 ("Rewritten Joshua")

- 4Q127 ("Rewritten Exodus")

- 4Q128-148 (various tefillin)

- 4Q156 ("Targum of Leviticus")

- 4Q157 ("Targum of Job") = 4QtgJob

- 4Q158, 364-367 ("Rewritten Pentateuch")

- 4Q161-164 ("Pesher on Isaiah")

- 4Q166-167 ("Pesher on Hosea")

- 4Q169 ("Pesher on Nahum")

- 4Q174 ("Florilegium" or "Midrash on the Last Days")

- 4Q175 ("Messianic Anthology" or "Testimonia")

- 4Q179 ("Lamentations") cf. 4Q501

- 4Q196-200 ("Tobit")

- 4Q213-214 ("Aramaic Levi")

- 4Q215 ("Testament of Naphtali")

- 4QCanta ("Pesher on Canticles or "Pesher on the Song of Songs") = 4Q240

- 4Q252 ("Pesher on Genesis")

- 4Q285 ("Rule of War") cf. 11Q14

- 4Q434 ("Barkhi Napshi - Apocryphal Psalms") (15 fragments likely hymns of thanksgiving, praising God for his power and expressing thanks )

- 4QMMT ("Miqsat Ma'ase Ha-Torah" or "MMT" or "Some Precepts of the Law" or the "Halakhic Letter") cf. 4Q394-399

- 4Q400-407 ("Songs of Sabbath Sacrifice" or the "Angelic Liturgy") cf. 11Q5-6

- 4Q448 ("Hymn to King Jonathan")

- 4Q521 ("Messianic Apocalypse")

- 4Q539 ("Testament of Joseph")

- 4Q554-5 ("New Jerusalem") cf. 1Q32, 2Q24, 5Q15, 11Q18

- 7Q2 ("Letter of Jeremiah") = Baruch 6

- 11QPsa ("Apocryphal Psalms") = 11Q5

- 11QtgJob ("Targum of Job") = 11Q10

- 11QMelch ("Heavenly Prince Melchizedek") = 11Q13

- 11QSM ("Sefer Ha-Milhamah" or "Book Of War") = 11Q14. cf. 1QM?

- 11QT ("Temple Scroll") = 11Q19

Significance to the Canon of the Bible

The significance of the scrolls relates in a large part to the field of textual criticism. Before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the oldest Hebrew manuscripts of the Bible were Masoretic texts dating to 9th century AD. The biblical manuscripts found among the Dead Sea Scrolls push that date back a millennium to the 2nd century BC. Before this discovery, the earliest extant manuscripts of the Old Testament were in Greek in manuscripts such as Codex Vaticanus Graecus 1209 and Codex Sinaiticus.

About 35% of the DSS biblical manuscripts belong to the Masoretic tradition, 5% to the Septuagint family, and 5% to the Samaritan, with the remainder unaligned. The non-aligned fall into two categories, those inconsistent in agreeing with other known types, and those that diverge significantly from all other known readings. The DSS thus form a significant witness to the mutability of biblical texts at this period.<ref>Emanuel Tov, "Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible" (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2001 2nd revised edition) ISBN 0800634292</ref> The sectarian texts among the Dead Sea Scrolls, most of which were previously unknown, offer new light on one form of Judaism practiced during the Second Temple period.

Frequency of books found

Books Ranked According to Number of Manuscripts found (top 16)<ref>Gaster, Theodor H., The Dead Sea Scriptures, Peter Smith Pub Inc., 1976. ISBN=0-8446-6702-1</ref>

| Books | No. found |

|---|---|

| Psalms | 39 |

| Deuteronomy | 33 |

| 1 Enoch | 25 |

| Genesis | 24 |

| Isaiah | 22 |

| Jubilees | 21 |

| Exodus | 18 |

| Leviticus | 17 |

| Numbers | 11 |

| Minor Prophets | 10 |

| Daniel | 8 |

| Jeremiah | 6 |

| Ezekiel | 6 |

| Job | 6 |

| 1 & 2 Samuel | 4 |

Origin of the Scrolls

There has been much debate about the origin of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The dominant theory remains that the scrolls were the product of a sect of Jews living at nearby Qumran called the Essenes, but this theory has come to be challenged by several modern scholars. The various theories concerning the origin of the scrolls are as follows:

Qumran-Essene Theory

The prevalent view among scholars, almost universally held until the 1990s, is the "Qumran-Essene" hypothesis originally posited by Roland Guérin de Vaux<ref>de Vaux, Roland, Archaeology and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Schweich Lectures of the British Academy, 1959). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973.</ref> and Józef Tadeusz Milik,<ref>Milik, Józef Tadeusz, Ten Years of Discovery in the Wilderness of Judea, London: SCM, 1959.</ref> though independently both Eliezer Sukenik and Butrus Sowmy of St Mark's Monastery connected scrolls with the Essenes well before any excavations at Qumran.<ref>For Sowmy, see: Trever, John C., The Untold Story of Qumran, (Westwood: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1965), p.25.</ref> The Qumran-Essene theory holds that the scrolls were written by the Essenes, or perhaps by another Jewish sectarian group, residing at Khirbet Qumran. They composed the scrolls and ultimately hid them in the nearby caves during the Jewish Revolt sometime between 66 and 68 CE. The site of Qumran was destroyed and the scrolls were never recovered by those that placed them there. A number of arguments are used to support this theory.

- There are striking similarities between the description of an initiation ceremony of new members in the Community Rule and descriptions of the Essene initiation ceremony mentioned in the works of Flavius Josephus' (a Jewish-Roman historian of the time) account of the Second Temple Period.

- Josephus mentions the Essenes as sharing property among the members of the community, as does the Community Rule.

- During the excavation of Khirbet Qumran, two inkwells and plastered elements thought to be tables were found, offering evidence that some form of writing was done there. More inkwells were discovered in nearby loci. De Vaux called this area the "scriptorium" based upon this discovery.

- Several Jewish ritual baths (Hebrew: miqvah = מקוה) were discovered at Qumran, which offers evidence of an observant Jewish presence at the site.

- Pliny the Elder (a geographer writing after the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE) describes a group of Essenes living in a desert community on the northwest shore of the Dead Sea near the ruined town of 'Ein Gedi.

The Qumran-Essene theory has been the dominant theory since its initial proposal by Roland de Vaux and J.T. Milik. Recently, however, several other scholars have proposed alternative origins of the scrolls.

Qumran-Sectarian Theory

Qumran-Sectarian theories are variations on the Qumran-Essene theory. The main point of departure from the Qumran-Essene theory is hesitation to link the Dead sea Scrolls specifically with the Essenes. Most proponents of the Qumran-Sectarian theory understand a group of Jews living in or near Qumran to be responsible for the Dead Sea Scrolls, but do not necessarily conclude that the sectarians are Essenes.

Qumran-Sadducean Theory

A specific variation on the Qumran-Sectarian theory that has gained much recent popularity, is the work of Lawrence H. Schiffman who proposes that the community was led by a group of Zadokite priests (Sadducees).<ref>Schiffman, Lawrence H., Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls: their True Meaning for Judaism and Christianity, Anchor Bible Reference Library (Doubleday) 1995</ref> The most important document in support of this view is the "Miqsat Ma'ase Ha-Torah" (4QMMT), which cites purity laws (such as the transfer of impurities) identical to those attributed in rabbinic writings to the Sadducees. 4QMMT also reproduces a festival calendar that follows Sadducee principles for the dating of certain festival days.

Christian Origin Theory

A few scholars have argued that the Dead Sea Scrolls reflect similarities with the early Christian movement. While there are certainly some common characteristics shared between different Jewish sectarian groups, most scholars deny that there is any connection whatsoever between the Christians and the authors of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Still, Spanish Jesuit Josep O'Callaghan-Martínez has argued that one fragment (7Q5) preserves a portion of text from the New Testament Gospel of Mark 6:52-53.<ref>O'Callaghan-Martínez, Josep, Cartas Cristianas Griegas del Siglo V, Barcelona: E. Balmes, 1963.</ref> In recent years, Robert Eisenman has advanced the theory that some scrolls actually describe the early Christian community. Eisenman also attempted to relate the career of James the Just and the Apostle Paul / Saul of Tarsus to some of these documents.<ref>Eisenman, Robert H. James, the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. 1st American ed. New York: Viking, 1997.</ref> Barbara Thiering also supports the Christian Origin theory, but argues that Jesus of Nazareth is the Wicked Priest mentioned in the scrolls.<ref>Thiering, Barbara, E. Jesus and the Riddle of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Unblocking the Secrets of His Life Story. San Francisco: Harper, 1992.</ref>

Jerusalem Origin Theory

Some scholars have argued that the scrolls were the product of Jews living in Jerusalem, who hid the scrolls in the caves near Qumran while fleeing from the Romans during the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE. Karl Heinrich Rengstorf first proposed that the Dead Sea Scrolls originated at the library of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem.<ref>Rengstorf, Karl Heinrich. Hirbet Qumran und die Bibliothek vom Toten Meer. Translated by J. R. Wilkie. Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer, 1960.</ref> Later, Norman Golb suggested that the scrolls were the product of multiple libraries in Jerusalem, and not necessarily the Jerusalem Temple library.<ref>Golb, Norman, Who Wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls? The Search for the Secret of Qumran, New York: Scribner, 1995.</ref> Proponents of the Jerusalem Origin theory point to the diversity of thought and handwriting among the scrolls as evidence against a Qumran origin of the scrolls. Several archaeologists have also accepted an origin of the scrolls other than Qumran, including Yizhar Hirschfeld<ref>Hirschfeld, Yizhar, Qumran in Context: Reassessing the Archaeological Evidence, Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2004.</ref> and most recently Yizhak Magen and Yuval Peleg,<ref>Magen, Yizhak, and Yuval Peleg, The Qumran Excavations 1993-2004: Preliminary Report, JSP 6 (Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 2007)Download</ref> who all understand the remains of Qumran to be those of a Hasmonean fort that was reused during later periods.

Publication

Some of the documents were published early. All the writings in Cave 1 appeared in print between 1950 and 1956, those from eight other caves were released in 1963, and 1965 saw the publication of the Psalms Scroll from Cave 11. Their translations into English soon followed.

Although heralded as one of the great events in modern archaeology, the discovery of the scrolls is not without controversy. All the manuscripts were initially placed under the oversight of a committee of scholars appointed by the Jordanian Department of Antiquities. This responsibility was assumed by the Israel Antiquities Authority after 1967.<ref name=britan/>

Some have claimed that access to the scrolls has been monopolized. Most of the longer, more complete scrolls were published soon after their discovery. The majority of the scrolls, however, consists of tiny, brittle fragments, which were published at a pace considered by many to be excessively slow. Even more unsettling for some was the fact that access to the unpublished documents was severely limited to the editorial committee. In 1991, researchers at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, Ohio, announced the creation of a computer program that used previously published scrolls to reconstruct the unpublished texts. Officials at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, announced that they would allow researchers unrestricted access to the library’s complete set of photographs of the scrolls. With their monopoly broken, the officials of the Israel Antiquities Authority agreed to lift their long-standing restrictions on the use of the scrolls.<ref name=britan>http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/154274/Dead-Sea-Scrolls</ref>

Ben Zion Wacholder's publication in the fall of 1991 of reconstructed 17 documents from a concordance that had been made in 1988 and had come into the hands of scholars outside of the International Team; in the same month, there occurred the discovery and publication of a complete set of facsimiles of the Cave 4 materials at the Huntington Library, which were not covered by the "secrecy rule".

After further delays, public interest attorney William John Cox undertook representation of an "undisclosed client," who had provided a complete set of the unpublished photographs, and contracted for their publication. Professors Robert Eisenman and James Robinson indexed the photographs and wrote an introduction to A Facsimile Edition of the Dead Sea Scrolls, which was published by the Biblical Archaeology Society in 1991.<ref>Eisenman, Robert H. and James Robinson, A Facsimile Edition of the Dead Sea Scrolls' in two volumes (Biblical Archaeology Society of Washington, DC, Washington, DC, 1991)</ref> As a result, the "secrecy rule" was lifted.

Publication accelerated with the appointment of the respected Dutch-Israeli textual scholar Emanuel Tov as editor-in-chief in 1990. Publication of the Cave 4 documents soon commenced, with five volumes in print by 1995. As of March 2009 volume XXXII remains to be completed, with the whole series, Discoveries in the Judean Desert, running to thirty nine volumes in total.

In December 2007, the Dead Sea Scrolls Foundation commissioned London publisher Facsimile Editions to publish exact facsimiles <ref>{{#invoke:citation/CS1|citation |CitationClass=web }}</ref> of three scrolls,<ref>{{#invoke:citation/CS1|citation |CitationClass=web }}</ref> The Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsa), The Order of the Community (1QS), and The Pesher to Habakkuk (1QpHab). Of the first three facsimile sets, one was exhibited at the Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls exhibition in Seoul, South Korea, and a second set was purchased by the British Library in London. A further 25 sets including facsimiles of fragments 4Q175 (Testimonia), 4Q162 (Pesher Isaiahb) and 4Q109 (Qohelet) were announced in May 2009.

The display of the scrolls has at times attracted controversy. In 2009, when the Israeli Antiquities Authority displayed the scrolls at the Royal Ontario Museum, the Palestinian Authority protested, claiming they were illegally obtained by Israel from the Jordanian-owned Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem in 1967.<ref>Template:Cite news</ref>

Digital copies

High-resolution images of all the Dead Sea Scrolls are not yet known to be available online. However, they can be purchased in inexpensive multi-volumes - on disc media or in book form - or viewed in certain college and university libraries.

According to Computer Weekly (16th Nov 2007), a team from King's College London is to advise the Israel Antiquities Authority, who are planning to digitize the scrolls. On 27th Aug 2008 an Israeli internet news agency YNET announced that the project is under way<ref>{{#invoke:citation/CS1|citation |CitationClass=web }}</ref>. The scrolls are planned to be made available to the public via Internet. The project is to include infra-red scanning of the scrolls which is said to expose additional details not revealed under visible light.

The text of nearly all of the non-biblical scrolls has been recorded and tagged for morphology by Dr. Martin Abegg, Jr., the Ben Zion Wacholder Professor of Dead Sea Scroll Studies at Trinity Western University in Langley, BC, Canada. It is available on handheld devices through Olive Tree Bible Software - BibleReader, on Macs through Accordance, and on Windows through Logos Bible Software and BibleWorks.

See also

- École Biblique - from which came one of the initial translation teams

- Josephus

- Nag Hammadi library

- Septuagint

- Tanakh at Qumran

- The Book of Mysteries

- Teacher of Righteousness

- Ugarit religious documents

- Wicked Priest

References

Notes

1.^ From papyrus to cyberspace The Guardian August 27, 2008. 2.^ Bruce, F. F.. "The Last Thirty Years". Story of the Bible. ed. Frederic G. Kenyon Retrieved June 19, 2007 3.^ Ilani, Ofri, "Scholar: The Essenes, Dead Sea Scroll 'authors,' never existed, Ha'aretz, March 13, 2009 4.^ Larson, Martin A, The Story of Christian Origins, Washington, D.C., New Republic Books, 1977 ppg 227-228 5.^ Larson, Martin A, The Story of Christian Origins, Washington, D.C., New Republic Books, 1977 ppg 236-246 6.^ Larson, Martin A, The Story of Christian Origins, Washington, D.C., New Republic Books, 1977 pg 240 7.^ Abegg, Jr., Martin, Peter Flint, and Eugene Ulrich, The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible: The Oldest Known Bible Translated for the First Time into English, San Francisco: Harper, 2002 8.^ Fagan, Brian M., and Charlotte Beck, The Oxford Companion to Archeology, entry on the "Dead sea scrolls", Oxford University Press, 1996 9.^ a b John C. Trever. The Dead Sea Scrolls. Gorgias Press LLC, 2003 10.^ a b "Iron-gall ink was the most important ink in Western history". realscience.breckschool.org. http://realscience.breckschool.org/upper/fruen/files/Enrichmentarticles/files/IronGallInk/IronGallInk.html. Retrieved 2008-12-29. 11.^ VanderKam, James C., The Dead Sea Scrolls Today, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994. p. 9. 12.^ a b Vermes, Geza, The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English, London: Penguin, 1998. ISBN 0-14-024501-4 13.^ a b VanderKam, James C., The Dead Sea Scrolls Today, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994. p. 10. 14.^ a b VanderKam, James C., The Dead Sea Scrolls Today, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994. p. 10-11. 15.^ Baillet, Maurice ed. Les ‘Petites Grottes’ de Qumrân (ed., vol. 3 of Discoveries in the Judean Desert; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1962), 144–45, pl. XXX. 16.^ Muro, Ernest A., “The Greek Fragments of Enoch from Qumran Cave 7 (7Q4, 7Q8, &7Q12 = 7QEn gr = Enoch 103:3–4, 7–8),” Revue de Qumran 18 no. 70 (1997). 17.^ Puech, Émile, “Sept fragments grecs de la Lettre d’Hénoch (1 Hén 100, 103, 105) dans la grotte 7 de Qumrân (= 7QHén gr),” Revue de Qumran 18 no. 70 (1997). 18.^ a b c Humbert and Chambon, Excavations of Khirbet Qumran and Ain Feshkha, 67. 19.^ Baillet ed. Les ‘Petites Grottes’ de Qumrân (ed.), 147–62, pl. XXXIXXXV. 20.^ Wexler, Lior ed. Surveys and Excavations of Caves in the Northern Judean Desert (CNJD) - 1993 (‘Atiqot 41; 2 vols.; Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 2002). 21.^ Magen, Yizhak and Yuval Peleg, The Qumran Excavations 1993–2004: Preliminary Report (Judea & Samaria Publications 6; Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 2007), 7. 22.^ Stegemann, Hartmut. "The Qumran Essenes: Local Members of the Main Jewish Union in Late Second Temple Times." Pages 83-166 in The Madrid Qumran Congress: Proceedings of the International Congress on the Dead Sea Scrolls, Madrid, 18-21 March 1991, Edited by J. Trebolle Barrera and L. Vegas Montaner. Vol. 11 of Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah. Leiden: Brill, 1992. 23.^ Emanuel Tov, "Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible" (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2001 2nd revised edition) ISBN 0800634292 24.^ Gaster, Theodor H., The Dead Sea Scriptures, Peter Smith Pub Inc., 1976. ISBN=0-8446-6702-1 25.^ de Vaux, Roland, Archaeology and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Schweich Lectures of the British Academy, 1959). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973. 26.^ Milik, Józef Tadeusz, Ten Years of Discovery in the Wilderness of Judea, London: SCM, 1959. 27.^ For Sowmy, see: Trever, John C., The Untold Story of Qumran, (Westwood: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1965), p.25. 28.^ Schiffman, Lawrence H., Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls: their True Meaning for Judaism and Christianity, Anchor Bible Reference Library (Doubleday) 1995 29.^ O'Callaghan-Martínez, Josep, Cartas Cristianas Griegas del Siglo V, Barcelona: E. Balmes, 1963. 30.^ Eisenman, Robert H. James, the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. 1st American ed. New York: Viking, 1997. 31.^ Thiering, Barbara, E. Jesus and the Riddle of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Unblocking the Secrets of His Life Story. San Francisco: Harper, 1992. 32.^ Rengstorf, Karl Heinrich. Hirbet Qumran und die Bibliothek vom Toten Meer. Translated by J. R. Wilkie. Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer, 1960. 33.^ Golb, Norman, Who Wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls? The Search for the Secret of Qumran, New York: Scribner, 1995. 34.^ Hirschfeld, Yizhar, Qumran in Context: Reassessing the Archaeological Evidence, Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2004. 35.^ Magen, Yizhak, and Yuval Peleg, The Qumran Excavations 1993-2004: Preliminary Report, JSP 6 (Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 2007)Download 36.^ a b http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/154274/Dead-Sea-Scrolls 37.^ Eisenman, Robert H. and James Robinson, A Facsimile Edition of the Dead Sea Scrolls' in two volumes (Biblical Archaeology Society of Washington, DC, Washington, DC, 1991) 38.^ "The Dead Sea Scrolls - A Limited Facsimile Edition". Facsimile Editions London. http://www.facsimile-editions.com/en/ds. 39.^ Rocker, Simon (2007-11-16). "The Dead Sea Scrolls...made in St John’s Wood". The Jewish Chronicle. http://website.thejc.com/home.aspx?ParentId=m13s100&AId=56661. Retrieved 2009-02-11. 40.^ "Dead Sea Scrolls ready for Canadian exhibit". 2009-06-25. http://www.cbc.ca/arts/artdesign/story/2009/06/25/dead-sea-scrolls-rom-show.html. 41.^ "(Hebrew) The Dead Sea Scrolls Being Exposed". YNET. 2008-08-27. http://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-3588523,00.html. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

Bibliography

- Abegg, Jr., Martin, Peter Flint, and Eugene Ulrich, The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible: The Oldest Known Bible Translated for the First Time into English, San Francisco: Harper, 2002. ISBN 0-06-060064-0, (contains the biblical portion of the scrolls)

- Abegg, Jr. Martin, James E. Bowley, Edward M. Cook, Emanuel Tov. The Dead Sea Scrolls Concordance, Vol 1.[1] Brill Publishing 2003. ISBN 9004125213.

- Allegro, John Marco, The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Christian Myth (ISBN 0-7153-7680-2), Westbridge Books, U.K., 1979.*Edward M. Cook, Solving the Mysteries of the Dead Sea Scrolls: New Light on the Bible, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1994.

- Boccaccini, Gabriele. Beyond the Essene Hypothesis: The Parting of Ways between Qumran and Enochic Judaism, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998.

- Charlesworth, James H. "The Theologies of the Dead Sea Scrolls." Pages xv-xxi in The Faith of Qumran: Theology of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Edited by H. Ringgren. New York: Crossroad, 1995.

- Collins, John J., Apocalypticism in the Dead Sea Scrolls, New York: Routledge, 1997.

- Collins, John J., and Craig A. Evans. Christian Beginnings and the Dead Sea Scrolls, Grand Rapids: Baker, 2006.

- Cross, Frank Moore, The Ancient Library of Qumran, 3rd ed., Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1995. ISBN 0-8006-2807-1

- Davies, A. Powell, The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls. (Signet, 1956.)

- Davies, Philip R., George J. Brooke, and Phillip R. Callaway, The Complete World of the Dead Sea Scrolls, London: Thames & Hudson, 2002. ISBN 0-500-05111-9

- de Vaux, Roland, Archaeology and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Schweich Lectures of the British Academy, 1959). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973.

- Dimant, Devorah, and Uriel Rappaport (eds.), The Dead Sea Scrolls: Forty Years of Research, Leiden and Jerusalem: E. J. Brill, Magnes Press, Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi, 1992.

- Eisenman, Robert H., The Dead Sea Scrolls and the First Christians, Shaftesbury: Element, 1996.

- Eisenman, Robert H., and Michael O. Wise. The Dead Sea Scrolls Uncovered: The First Complete Translation and Interpretation of 50 Key Documents Withheld for Over 35 Years, Shaftesbury: Element, 1992.

- Eisenman, Robert H. and James Robinson, A Facsimile Edition of the Dead Sea Scrolls 2 vol., Washington, D.C.: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1991.

- Fitzmyer, Joseph A., Responses to 101 Questions on the Dead Sea Scrolls, Paulist Press 1992, ISBN 0-8091-3348-2

- Galor, Katharina, Jean-Baptiste Humbert, and Jürgen Zangenberg. Qumran: The Site of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Archaeological Interpretations and Debates: Proceedings of a Conference held at Brown University, November 17-19, 2002, Edited by Florentino García Martínez, Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah 57. Leiden: Brill, 2006.

- García-Martinez, Florentino, The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, (Translated from Spanish into English by Wilfred G. E. Watson) (Leiden: E.J.Brill, 1994).

- Gaster, Theodor H., The Dead Sea Scriptures, Peter Smith Pub Inc., 1976. ISBN=0-8446-6702-1

- Golb, Norman, Who Wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls? The Search for the Secret of Qumran, New York: Scribner, 1995.

- Heline, Theodore, Dead Sea Scrolls, New Age Bible & Philosophy Center, 1957, Reprint edition March 1987, ISBN 0-933963-16-5

- Hirschfeld, Yizhar, Qumran in Context: Reassessing the Archaeological Evidence, Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2004.

- Israeli, Raphael, Piracy in Qumran: The Battle over the Scrolls of the Pre-Christ Era, Transaction Publishers: 2008 ISBN 978-1-4128-0703-6

- Khabbaz, C., "Les manuscrits de la mer Morte et le secret de leurs auteurs",Beirut, 2006. (Ce livre identifie les auteurs des fameux manuscrits de la mer Morte et dévoile leur secret).

- Magen, Yizhak, and Yuval Peleg, The Qumran Excavations 1993-2004: Preliminary Report, JSP 6 (Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 2007)Download

- Magen, Yizhak, and Yuval Peleg, "Back to Qumran: Ten years of Excavations and Research, 1993-2004," in The Site of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Archaeological Interpretations and Debates (Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah 57), Brill, 2006 (pp. 55–116).

- Magness, Jodi, The Archaeology of Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002.

- Maier, Johann, The Temple Scroll, [German edition was 1978], (Sheffield:JSOT Press [Supplement 34], 1985).

- Milik, Józef Tadeusz, Ten Years of Discovery in the Wilderness of Judea, London: SCM, 1959.

- Muro, E. A., "The Greek Fragments of Enoch from Qumran Cave 7 (7Q4, 7Q8, &7Q12 = 7QEn gr = Enoch 103:3-4, 7-8)." Revue de Qumran 18, no. 70 (1997): 307, 12, pl. 1.

- O'Callaghan-Martínez, Josep, Cartas Cristianas Griegas del Siglo V, Barcelona: E. Balmes, 1963.

- Qimron, Elisha, The Hebrew of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Harvard Semitic Studies, 1986. (This is a serious discussion of the Hebrew language of the scrolls.)

- Rengstorf, Karl Heinrich, Hirbet Qumran und die Bibliothek vom Toten Meer, Translated by J. R. Wilkie. Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer, 1960.

- Roitman, Adolfo, ed. A Day at Qumran: The Dead Sea Sect and Its Scrolls. Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 1998.

- Sanders, James A., ed. Dead Sea scrolls: The Psalms scroll of Qumrân Cave 11 (11QPsa), (1965) Oxford, Clarendon Press.

- Schiffman,Lawrence H., Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls: their True Meaning for Judaism and Christianity, Anchor Bible Reference Library (Doubleday) 1995, ISBN 0-385-48121-7, (Schiffman has suggested two plausible theories of origin and identity - a Sadducean splinter group, or perhaps an Essene group with Sadducean roots.) Excerpts of this book can be read at COJS: Dead Sea Scrolls.

- Schiffman, Lawrence H., and James C. VanderKam, eds. Encyclopedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls. 2 vols. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Shanks, Hershel, The Mystery and Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Vintage Press 1999, ISBN 0-679-78089-0 (recommended introduction to their discovery and history of their scholarship)

- Stegemann, Hartmut. "The Qumran Essenes: Local Members of the Main Jewish Union in Late Second Temple Times." Pages 83–166 in The Madrid Qumran Congress: Proceedings of the International Congress on the Dead Sea Scrolls, Madrid, 18-21 March 1991, Edited by J. Trebolle Barrera and L. Vegas Mountainer. Vol. 11 of Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah. Leiden: Brill, 1992.

- Thiede, Carsten Peter, The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Jewish Origins of Christianity, PALGRAVE 2000, ISBN 0-312-29361-5

- Thiering, Barbara, Jesus the Man, New York: Atria, 2006.

- Thiering, Barbara, Jesus and the Riddle of the Dead Sea Scrolls (ISBN 0-06-067782-1), New York: Harper Collins, 1992

- VanderKam, James C., The Dead Sea Scrolls Today, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994.

- Vermes, Geza, The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English, London: Penguin, 1998. ISBN 0-14-024501-4 (good translation, but complete only in the sense that he includes translations of complete texts, but neglects fragmentary scrolls and more especially does not include biblical texts.)

- Wise, Michael O., Martin Abegg, Jr., and Edward Cook, The Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Translation, (1996), HarperSanFrancisco paperback 1999, ISBN 0-06-069201-4, (contains the non-biblical portion of the scrolls, including fragments)

- Yadin, Yigael. The Temple Scroll: The Hidden Law of the Dead Sea Sect, New York: Random House, 1985.

Other sources

- Dead Sea Scrolls Study Vol 1: 1Q1-4Q273, Vol. 2: 4Q274-11Q31, (compact disc), Logos Research Systems, Inc., (contains the non-biblical portion of the scrolls with Hebrew and Aramaic transcriptions in parallel with English translations)

External links

- Dead Sea Scrolls facsimile of 1QIsa 1Qs and 1QpHab - see also Facsimile

- UCLA Qumran Visualization Project

- Timetable of the Discovery and Debate about the Dead Sea Scrolls

- Dead Sea Scrolls & Qumran

- The Dead Sea Scrolls (FARMS)

- The Dead Sea Scrolls and Why They Matter

- Some of the scrolls can be seen inside the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem

- Scrolls From the Dead Sea: The Ancient Library of Qumran and Modern Scholarship at Library of Congress

- Library of Congress On-line Exhibit

- The Dead Sea Scrolls Project at the Oriental Institute features several articles by Norman Golb, some of which take issue with statements made in popular museum exhibits of the Dead Sea Scrolls

- Guide with Hyperlinked Background Material to the Exhibit Ancient Treasures and the Dead Sea Scrolls Canadian Museum of Civilization

- Dead Sea Scrolls @ the Royal Ontario Museum

- The Importance of the Discoveries in the Judean Desert Israel Antiquities Authority

- F.F Bruce, Second Thoughts on the Dead Sea Scrolls (1956) On-line book (PDF).

- The Pesher of Christ: Dr. Barbara Thiering's Writings Barbara Thiering's (unconventional) theories connecting the scrolls with the Bible

- Orion Center for the Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, includes updated bibliography.

- "Jannaeus, His Brother Absalom, and Judah the Essene," Stephen Goranson, on Teacher of Righteousness and Wicked Priest identities.

- "Others and Intra-Jewish Polemic as Reflected in Qumran Texts," Stephen Goranson, evidence that English "Essenes" comes from Greek spellings that come from Hebrew 'osey hatorah, a self-designation in some Qumran texts.