The Praise of Folly

From Textus Receptus

(→See Also) |

|||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

The essay is filled with classical allusions delivered in a style typical of the learned humanists of the [[Renaissance]]. Folly parades as one of the gods, offspring of Plutos and Freshness and nursed by Inebriation and Ignorance, whose faithful companions include Philautia (self-love), Kolakia (flattery), [[Lethe]] (oblivion), Misoponia (laziness), Hedone (pleasure), Anoia (madness), [[Tryphé | Tryphe]] (wantonness), Komos (intemperance) and Eegretos Hypnos (dead sleep). | The essay is filled with classical allusions delivered in a style typical of the learned humanists of the [[Renaissance]]. Folly parades as one of the gods, offspring of Plutos and Freshness and nursed by Inebriation and Ignorance, whose faithful companions include Philautia (self-love), Kolakia (flattery), [[Lethe]] (oblivion), Misoponia (laziness), Hedone (pleasure), Anoia (madness), [[Tryphé | Tryphe]] (wantonness), Komos (intemperance) and Eegretos Hypnos (dead sleep). | ||

| + | |||

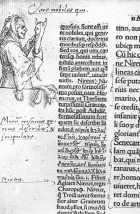

| + | ''Moriae Encomium'' was hugely popular, to Erasmus' astonishment and sometimes his dismay. [[Pope Leo X|Leo X]] thought it was funny. Before Erasmus' death it had already passed into numerous editions and had been translated into [[French]] and [[German]]. An [[English]] edition soon followed. It influenced teaching of [[rhetoric]] during the later sixteenth century, and the art of [[adoxography]] or praise of worthless subjects became a popular exercise in Elizabethan grammar schools: see Charles O. McDonald, ''The Rhetoric of Tragedy'' (Amherst, 1966). A copy of the [[Basel]] edition of 1515/16 was illustrated with pen and ink [[drawing]]s by [[Hans Holbein the Younger]].<sup>[1]</sup> These are the most famous illustrations of ''The Praise of Folly''. | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

* [[The Praise of Folly by Desiderius Erasmus]] | * [[The Praise of Folly by Desiderius Erasmus]] | ||

| - | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

Revision as of 11:47, 13 February 2011

The Praise of Folly (Greek title: Morias Enkomion (Μωρίας Εγκώμιον), Latin: Stultitiae Laus, sometimes translated as In Praise of More, Dutch title: Lof der Zotheid) is an essay written in 1509 by Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam and first printed in 1511. The essay was inspired by De Triumpho Stultitiae, written by Italian humanist Faustino Perisauli, born at Tredozio, near Forlì.

Erasmus revised and extended the work, which he originally wrote in the space of a week while sojourning with Sir Thomas More at More's estate in Bucklersbury. In Praise of Folly is considered one of the most notable works of the Renaissance and one of the catalysts of the Protestant Reformation.

It starts off with a satirical learned encomium after the manner of the Greek satirist Lucian, whose work Erasmus and Sir Thomas More had recently translated into Latin, a piece of virtuoso foolery; it then takes a darker tone in a series of orations, as Folly praises self-deception and madness and moves to a satirical examination of pious but superstitious abuses of Catholic doctrine and corrupt practices in parts of the Roman Catholic Church—to which Erasmus was ever faithful—and the folly of pedants (including Erasmus himself). Erasmus had recently returned disappointed from Rome, where he had turned down offers of advancement in the curia, and Folly increasingly takes on Erasmus' own chastising voice. The essay ends with a straightforward statement of Christian ideals.

Erasmus was a good friend of More, with whom he shared a taste for dry humor and other intellectual pursuits. The title "Moriae Encomium" can also be read as meaning "In praise of More". The double or triple meanings go on throughout the text.

The essay is filled with classical allusions delivered in a style typical of the learned humanists of the Renaissance. Folly parades as one of the gods, offspring of Plutos and Freshness and nursed by Inebriation and Ignorance, whose faithful companions include Philautia (self-love), Kolakia (flattery), Lethe (oblivion), Misoponia (laziness), Hedone (pleasure), Anoia (madness), Tryphe (wantonness), Komos (intemperance) and Eegretos Hypnos (dead sleep).

Moriae Encomium was hugely popular, to Erasmus' astonishment and sometimes his dismay. Leo X thought it was funny. Before Erasmus' death it had already passed into numerous editions and had been translated into French and German. An English edition soon followed. It influenced teaching of rhetoric during the later sixteenth century, and the art of adoxography or praise of worthless subjects became a popular exercise in Elizabethan grammar schools: see Charles O. McDonald, The Rhetoric of Tragedy (Amherst, 1966). A copy of the Basel edition of 1515/16 was illustrated with pen and ink drawings by Hans Holbein the Younger.[1] These are the most famous illustrations of The Praise of Folly.

See Also

Notes

External links

- Praise of Folly, translated by John Wilson in 1668, at Project Gutenberg

- Praise of Folly at Internet Archive (scanned books original editions)

- Praise of Folly, English translation published in 1922.

- The Praise of Folly — Google Books, full view!