Curetonian Gospels

From Textus Receptus

(→Text) |

(→Text) |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

:"This very small remaining Fragment of St. Mark is an early testimony to the authenticity of the last twelve verses of this Gospel, which have been deemed spurious by some critics." | :"This very small remaining Fragment of St. Mark is an early testimony to the authenticity of the last twelve verses of this Gospel, which have been deemed spurious by some critics." | ||

| - | In 1912, Sir Frederic Kenyon can still say of this fragment, that it "is sufficient to show that it contained the last twelve verses of the Gospel." (Handbook to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament, 2d ed., London, 1912, P. 1550 | + | In 1912, Sir Frederic Kenyon can still say of this fragment, that it "is sufficient to show that it contained the last twelve verses of the Gospel." (Handbook to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament, 2d ed., London, 1912, P. 1550) |

== History == | == History == | ||

Revision as of 04:16, 21 February 2015

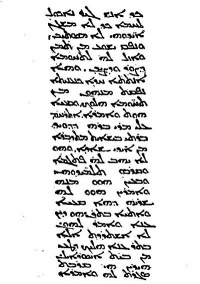

The Curetonian Gospels, designated by the siglum syrcur, are contained in a manuscript of the four gospels of the New Testament in Old Syriac. Together with the Sinaiticus Palimpsest the Curetonian Gospels form the Old Syriac Version, and are known as the Evangelion Dampharshe ("Separated Gospels") in the Syriac Church.[1]

The Gospels are commonly named after William Cureton who maintained that they represented an Aramaic Gospel and had not been translated from Greek (1858)[2] and differed considerably from the canonical Greek texts, with which they had been collated and "corrected". Henry Harman (1885) concluded, however, that their originals had been Greek from the outset.[3] The order of the gospels is Matthew, Mark, John, Luke. The text is one of only two Syriac manuscripts of the separate gospels that possibly predate the standard Syriac version, the Peshitta; the other is the Sinaitic Palimpsest. A fourth Syriac text is the harmonized Diatessaron. The Curetonian Gospels and the Sinaitic Palimpsest appear to have been translated from independent Greek originals.[4]

Contents |

Text

The Syriac text of the codex is a representative of the Western text. Significant variant readings include:

- In Matthew 4:23 the variant "in whole Galilee" together with Codex Vaticanus Graecus 1209, Codex Bobiensis, ℓ 20 and copsa.

- Matthew 12:47 is omitted.[5]

- In Matthew 16:12 the variant leaven of bread of the Pharisees and Sadducees supported only by Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Corbeiensis I.

- In Luke 23:43 the variant I say today to you, you will be with me in paradise supported only by unspaced dot in Codex Vaticanus and lack of punctuation in earlier Greek MSS.[6]

The Book of Mark is missing except for verses 17-20 in the last chapter. It reads:

- .. .that believe in me; these in my name shall cast out de mons; with new tongues they shall speak; serpents they

shall take up in their hands; and if any poison of death they drink, it shall not hurt them; on the diseased they shall lay their hands, and they shall become sound. But our Lord Jesus, after that he had commanded his disciples, was exalted to heaven, and sat on the right [hand] of God. But they went forth, and preached in every place, and the Lord [was] with them in all, and their word he was confirming by the signs which they were doing. Endeth Gospel of Mark.

In the first edition of this Version (London, 1858, p.xliv) William Cureton, its discoverer, said:

- "This very small remaining Fragment of St. Mark is an early testimony to the authenticity of the last twelve verses of this Gospel, which have been deemed spurious by some critics."

In 1912, Sir Frederic Kenyon can still say of this fragment, that it "is sufficient to show that it contained the last twelve verses of the Gospel." (Handbook to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament, 2d ed., London, 1912, P. 1550)

History

The manuscript gets its curious name from being edited and published by William Cureton in 1858. The manuscript was among a mass of manuscripts brought in 1842 from a Syrian monastery in the Wadi Natroun, Lower Egypt, as the result of a series of negotiations that had been under way for some time; it is conserved in the British Library. Cureton recognized that the Old Syriac text of the gospels was significantly different from any known at the time. He dated the manuscript fragments to the fifth century; the text, which may be as early as the second century, is written in the oldest and classical form of the Syriac alphabet, called Esṭrangelā, without vowel points.[7]

In 1872 William Wright, of the University of Cambridge, privately printed about a hundred copies of further fragments, Fragments of the Curetonian Gospels, (London, 1872), without translation or critical apparatus. The fragments, bound as flyleaves in a Syriac codex in Berlin, once formed part of the Curetonian manuscript, and fill some of its lacunae.[8]

The publication of the Curetonian Gospels and the Sinaitic Palimpsest enabled scholars for the first time to examine how the gospel text in Syriac changed between the earliest period (represented by the text of the Sinai and Curetonian manuscripts) and the later period. The Syriac versions of the New Testament remain less thoroughly studied than the Greek.

The standard text is that of Francis Crawford Burkitt, 1904;[9] it was used in the comparative edition of the Syriac gospels that was edited by George Anton Kiraz, 1996.[10]

See also

Notes

- 1. Orthodox Resources. George Kiraz, 2001

- 2. Cureton, Remains of a Very Ancient Recension of the Four Gospels in Syriac, Hitherto Unknown in Europe, London, 1858; Cureton included an English translation of the newly discovered text, and a long introduction.

- 3. Henry Martyn Harman (1822-1897), "Cureton's fragments of Syriac Gospels" Journal of the Society of Biblical Literature and Exegesis 5.1/2 (June - December 1885), pp 28-48.

- 4. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft -Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft, Rudolf Anger, Hermann Brockhaus - 1951 Volume 101 - Page 125 "Their text was at least as old as the Curetonian ; they certainly were translated from Greek Gospels ; and they presented a number of strange readings, notably the reading ' Joseph begot Jesus," in Mt 1:16. There were critical problems here, ..."

- 5. Nestle-Aland, Novum Testamentum Graece 26th ed., p. 46.

- 6. UBS GNT

- 7. of a page.

- 8. Henry M. Harman, "Cureton's fragments of Syriac Gospels" Journal of the Society of Biblical Literature and Exegesis 5.1/2 (June - December 1885), pp 28-48.

- 9. Burkitt, Evangelion da-Mepharreshe, The Curetonian Version of the Four Gospels (Cambridge University Press) 1904.

- 10. Kiraz, Comparative Edition of the Syriac Gospels, Aligning the Syriac Sinaiticus, Curetonianus, Peshîttâ and Harklean Versions 4 vols. (Leiden: Brill) 1996.

References

- Harman, Henry M. "Cureton's Fragments of Syriac Gospels" Journal of the Society of Biblical Literature and Exegesis 5.1/2 (June-December 1885), pp. 28-48.

- Burkitt, F.C. Evangelion Da-Mepharreshe: The Curetonian Version of the Four Gospels, with the readings of the Sinai Palimpsest and the early Syriac Patristic evidence (Gorgias Press 2003) ISBN 978-1-59333-061-3 . This is the standard edition of the Curetonian manuscript, with the Sinai text in the footnotes. Volume I contains the Syriac text with facing English translation; volume II discusses the Old Syriac version.

- Kiraz, George Anton. Comparative Edition of the Syriac Gospels: Aligning the Sinaiticus, Curetonianus, Peshitta and Harklean Versions. Vol. 1: Matthew; vol. 2: Mark; vol.3: Luke; vol. 4: John. (Leiden: Brill), 1996. ISBN 90-04-10419-4 .

External links

- Thomas Nicol, "Syriac Versions of the Bible" A simplified on-line introduction.

- Curetonian Syriac